One of the largest wildfires in California history — the Rim Fire — threatens some of the most spectacular vistas in the U.S. Yet, as it reshaped part of Yosemite Valley and surroundings it is forcing another reshaping: a fundamental re-thinking of the wildland urban interface (WUI) and the role of human activity in catalyzing natural processes.

From Wired:

For nearly two weeks, the nation has been transfixed by wildfire spreading through Yosemite National Park, threatening to pollute San Francisco’s water supply and destroy some of America’s most cherished landscapes. As terrible as the Rim Fire seems, though, the question of its long-term effects, and whether in some ways it could actually be ecologically beneficial, is a complicated one.

Some parts of Yosemite may be radically altered, entering entire new ecological states. Yet others may be restored to historical conditions that prevailed for for thousands of years from the last Ice Age’s end until the 19th century, when short-sighted fire management disrupted natural fire cycles and transformed the landscape.

In certain areas, “you could absolutely consider it a rebooting, getting the system back to the way it used to be,” said fire ecologist Andrea Thode of Northern Arizona University. “But where there’s a high-severity fire in a system that wasn’t used to having high-severity fires, you’re creating a new system.”

The Rim Fire now covers 300 square miles, making it the largest fire in Yosemite’s recent history and the sixth-largest in California’s. It’s also the latest in a series of exceptionally large fires that over the last several years have burned across the western and southwestern United States.

Fire is a natural, inevitable phenomenon, and one to which western North American ecologies are well-adapted, and even require to sustain themselves. The new fires, though, fueled by drought, a warming climate and forest mismanagement — in particular the buildup of small trees and shrubs caused by decades of fire suppression — may reach sizes and intensities too severe for existing ecosystems to withstand.

The Rim Fire may offer some of both patterns. At high elevations, vegetatively dominated by shrubs and short-needled conifers that produce a dense, slow-to-burn mat of ground cover, fires historically occurred every few hundred years, and they were often intense, reaching the crowns of trees. In such areas, the current fire will fit the usual cycle, said Thode.

Decades- and centuries-old seeds, which have remained dormant in the ground awaiting a suitable moment, will be cracked open by the heat, explained Thode. Exposed to moisture, they’ll begin to germinate and start a process of vegetative succession that results again in forests.

At middle elevations, where most of the Rim Fire is currently concentrated, a different fire dynamic prevails. Those forests are dominated by long-needled conifers that produce a fluffy, fast-burning ground cover. Left undisturbed, fires occur regularly.

“Up until the middle of the 20th century, the forests of that area would burn very frequently. Fires would go through them every five to 12 years,” said Carl Skinner, a U.S. Forest Service ecologist who specializes in relationships between fire and vegetation in northern California. “Because the fires burned as frequently as they did, it kept fuels from accumulating.”

A desire to protect houses, commercial timber and conservation lands by extinguishing these small, frequent fires changed the dynamic. Without fire, dead wood accumulated and small trees grew, creating a forest that’s both exceptionally flammable and structurally suited for transferring flames from ground to tree-crown level, at which point small burns can become infernos.

Though since the 1970s some fires have been allowed to burn naturally in the western parts of Yosemite, that’s not the case where the Rim Fire now burns, said Skinner. An open question, then, is just how big and hot it will burn.

Where the fire is extremely intense, incinerating soil seed banks and root structures from which new trees would quickly sprout, the forest won’t come back, said Skinner. Those areas will become dominated by dense, fast-growing shrubs that burn naturally every few years, killing young trees and creating a sort of ecological lock-in.

If the fire burns at lower intensities, though, it could result in a sort of ecological recalibration, said Skinner. In his work with fellow U.S. Forest Service ecologist Eric Knapp at the Stanislaus-Tuolumne Experimental Forest, Skinner has found that Yosemite’s contemporary, fire-suppressed forests are actually far more homogeneous and less diverse than a century ago.

The fire could “move the forests in a trajectory that’s more like the historical,” said Skinner, both reducing the likelihood of large future fires and generating a mosaic of habitats that contain richer plant and animal communities.

“It may well be that, across a large landscape, certain plants and animals are adapted to having a certain amount of young forest recovering after disturbances,” said forest ecologist Dan Binkley of Colorado State University. “If we’ve had a century of fires, the landscape might not have enough of this.”

Read the entire article here.

Image: Rim Fire, August 2013. Courtesy of Earth Observatory, NASA.

Seamus Heaney, poet, Nobel Laureate and above all observer of the Irish condition passed away last week.

Seamus Heaney, poet, Nobel Laureate and above all observer of the Irish condition passed away last week. How does a design aesthetic save lives? It’s simpler than you might think. Take a basic medical syringe, add a twist of color-change technology, borrowed from the design world, and you get a device that can save 1.3 million lives each year.

How does a design aesthetic save lives? It’s simpler than you might think. Take a basic medical syringe, add a twist of color-change technology, borrowed from the design world, and you get a device that can save 1.3 million lives each year. Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney.

Enough is enough! Our favorite wordsmiths must call a halt right now. First we lost Chris Hitchens, soon followed by Iain Banks. And now, poet extraordinaire, Seamus Heaney. When asked about handedness Nick Moran over a TheMillions says, “everybody’s born right-handed, but the best overcome it.” Funny. And perhaps, now, based on several rings of truth.

When asked about handedness Nick Moran over a TheMillions says, “everybody’s born right-handed, but the best overcome it.” Funny. And perhaps, now, based on several rings of truth.![The beef was grown in a lab by a pioneer in this arena — Mark Post of Maastricht University in the Netherlands. My colleague Henry Fountain has reported the details in a fascinating news article. Here’s an excerpt followed by my thoughts on next steps in what I see as an important area of research and development: According to the three people who ate it, the burger was dry and a bit lacking in flavor. One taster, Josh Schonwald, a Chicago-based author of a book on the future of food [link], said “the bite feels like a conventional hamburger” but that the meat tasted “like an animal-protein cake.” But taste and texture were largely beside the point: The event, arranged by a public relations firm and broadcast live on the Web, was meant to make a case that so-called in-vitro, or cultured, meat deserves additional financing and research….. Dr. Post, one of a handful of scientists working in the field, said there was still much research to be done and that it would probably take 10 years or more before cultured meat was commercially viable. Reducing costs is one major issue — he estimated that if production could be scaled up, cultured beef made as this one burger was made would cost more than $30 a pound. The two-year project to make the one burger, plus extra tissue for testing, cost $325,000. On Monday it was revealed that Sergey Brin, one of the founders of Google, paid for the project. Dr. Post said Mr. Brin got involved because “he basically shares the same concerns about the sustainability of meat production and animal welfare.” The enormous potential environmental benefits of shifting meat production, where feasible, from farms to factories were estimated in “Environmental Impacts of Cultured Meat Production,”a 2011 study in Environmental Science and Technology.](http://cdn.theatlantic.com/newsroom/img/posts/RTX12B04.jpg)

If you live somewhere rather toasty you know how painful your electricity bills can be during the summer months. So, wouldn’t it be good to have a system automatically find you the cheapest electricity when you need it most? Welcome to the artificially intelligent smarter smart grid.

If you live somewhere rather toasty you know how painful your electricity bills can be during the summer months. So, wouldn’t it be good to have a system automatically find you the cheapest electricity when you need it most? Welcome to the artificially intelligent smarter smart grid. The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.

The majority of us can identify with the awkward and self-conscious years of adolescence. And, interestingly enough many of us emerge to the other side.

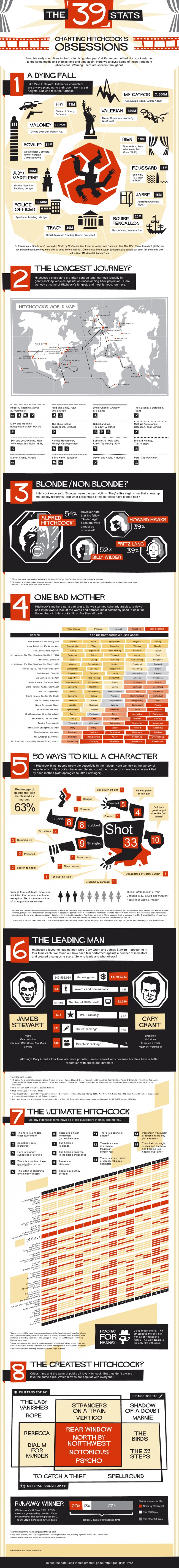

You could be forgiven for believing that celebrity is a peculiar and pervasive symptom of our contemporary culture. After all in our multi-channel, always on pop-culture, 24×7 event-driven, media-obsessed maelstrom celebrities come, and go, in the blink of an eye. This is the age of celebrity.

You could be forgiven for believing that celebrity is a peculiar and pervasive symptom of our contemporary culture. After all in our multi-channel, always on pop-culture, 24×7 event-driven, media-obsessed maelstrom celebrities come, and go, in the blink of an eye. This is the age of celebrity.

If you’re a professional or like networking, but shun Facebook, then chances are good that you hang-out on LinkedIn. And, as you do, the company is trawling through your personal data and that of hundreds of millions of other members to turn human resources and career planning into a science — all with the help of big data.

If you’re a professional or like networking, but shun Facebook, then chances are good that you hang-out on LinkedIn. And, as you do, the company is trawling through your personal data and that of hundreds of millions of other members to turn human resources and career planning into a science — all with the help of big data.

Unplugging from the conveniences and obsessions of our age can be difficult, but not impossible. For those of you who have a demanding boss or needful relationships or lack the will to do away with the email, texts, tweets, voicemail, posts, SMS, likes and status messages there may still be (some) hope without having to go completely cold turkey.

Unplugging from the conveniences and obsessions of our age can be difficult, but not impossible. For those of you who have a demanding boss or needful relationships or lack the will to do away with the email, texts, tweets, voicemail, posts, SMS, likes and status messages there may still be (some) hope without having to go completely cold turkey.

A new verb for a very recent phenomenon. Phubbing was invented by inveterate texters and proliferated by anyone aged between 16-25 years.

A new verb for a very recent phenomenon. Phubbing was invented by inveterate texters and proliferated by anyone aged between 16-25 years.