The quest for immortality or even great longevity has probably led humans since they first became self-aware. Entire cultural movements and industries are founded on the desire to enhance and extend our lives. Genetic research, of course, may eventually unlock some or all of life and death’s mysteries. In the meantime, groups of dedicated scientists continue to look for for the foundation of aging with a view to understanding the process and eventually slowing (and perhaps stopping) it. Richard Walker is one of these singularly focused researchers.

From the BBC:

Richard Walker has been trying to conquer ageing since he was a 26-year-old free-loving hippie. It was the 1960s, an era marked by youth: Vietnam War protests, psychedelic drugs, sexual revolutions. The young Walker relished the culture of exultation, of joie de vivre, and yet was also acutely aware of its passing. He was haunted by the knowledge that ageing would eventually steal away his vitality – that with each passing day his body was slightly less robust, slightly more decayed. One evening he went for a drive in his convertible and vowed that by his 40th birthday, he would find a cure for ageing.

Walker became a scientist to understand why he was mortal. “Certainly it wasn’t due to original sin and punishment by God, as I was taught by nuns in catechism,” he says. “No, it was the result of a biological process, and therefore is controlled by a mechanism that we can understand.”

Scientists have published several hundred theories of ageing, and have tied it to a wide variety of biological processes. But no one yet understands how to integrate all of this disparate information.

Walker, now 74, believes that the key to ending ageing may lie in a rare disease that doesn’t even have a real name, “Syndrome X”. He has identified four girls with this condition, marked by what seems to be a permanent state of infancy, a dramatic developmental arrest. He suspects that the disease is caused by a glitch somewhere in the girls’ DNA. His quest for immortality depends on finding it.

It’s the end of another busy week and MaryMargret Williams is shuttling her brood home from school. She drives an enormous SUV, but her six children and their coats and bags and snacks manage to fill every inch. The three big kids are bouncing in the very back. Sophia, 10, with a mouth of new braces, is complaining about a boy-crazy friend. She sits next to Anthony, seven, and Aleena, five, who are glued to something on their mother’s iPhone. The three little kids squirm in three car seats across the middle row. Myah, two, is mining a cherry slushy, and Luke, one, is pawing a bag of fresh crickets bought for the family gecko.

Finally there’s Gabrielle, who’s the smallest child, and the second oldest, at nine years old. She has long, skinny legs and a long, skinny ponytail, both of which spill out over the edges of her car seat. While her siblings giggle and squeal, Gabby’s dusty-blue eyes roll up towards the ceiling. By the calendar, she’s almost an adolescent. But she has the buttery skin, tightly clenched fingers and hazy awareness of a newborn.

Back in 2004, when MaryMargret and her husband, John, went to the hospital to deliver Gabby, they had no idea anything was wrong. They knew from an ultrasound that she would have clubbed feet, but so had their other daughter, Sophia, who was otherwise healthy. And because MaryMargret was a week early, they knew Gabby would be small, but not abnormally so. “So it was such a shock to us when she was born,” MaryMargret says.

Gabby came out purple and limp. Doctors stabilised her in the neonatal intensive care unit and then began a battery of tests. Within days the Williamses knew their new baby had lost the genetic lottery. Her brain’s frontal lobe was smooth, lacking the folds and grooves that allow neurons to pack in tightly. Her optic nerve, which runs between the eyes and the brain, was atrophied, which would probably leave her blind. She had two heart defects. Her tiny fists couldn’t be pried open. She had a cleft palate and an abnormal swallowing reflex, which meant she had to be fed through a tube in her nose. “They started trying to prepare us that she probably wouldn’t come home with us,” John says. Their family priest came by to baptise her.

Day after day, MaryMargret and John shuttled between Gabby in the hospital and 13-month-old Sophia at home. The doctors tested for a few known genetic syndromes, but they all came back negative. Nobody had a clue what was in store for her. Her strong Catholic family put their faith in God. “MaryMargret just kept saying, ‘She’s coming home, she’s coming home’,” recalls her sister, Jennie Hansen. And after 40 days, she did.

Gabby cried a lot, loved to be held, and ate every three hours, just like any other newborn. But of course she wasn’t. Her arms would stiffen and fly up to her ears, in a pose that the family nicknamed her “Harley-Davidson”. At four months old she started having seizures. Most puzzling and problematic, she still wasn’t growing. John and MaryMargret took her to specialist after specialist: a cardiologist, a gastroenterologist, a geneticist, a neurologist, an ophthalmologist and an orthopaedist. “You almost get your hopes up a little – ’This is exciting! We’re going to the gastro doctor, and maybe he’ll have some answers’,” MaryMargret says. But the experts always said the same thing: nothing could be done.

The first few years with Gabby were stressful. When she was one and Sophia two, the Williamses drove from their home in Billings, Montana, to MaryMargret’s brother’s home outside of St Paul, Minnesota. For nearly all of those 850 miles, Gabby cried and screamed. This continued for months until doctors realised she had a run-of-the-mill bladder infection. Around the same period, she acquired a severe respiratory infection that left her struggling to breathe. John and MaryMargret tried to prepare Sophia for the worst, and even planned which readings and songs to use at Gabby’s funeral. But the tiny toddler toughed it out.

While Gabby’s hair and nails grew, her body wasn’t getting bigger. She was developing in subtle ways, but at her own pace. MaryMargret vividly remembers a day at work when she was pushing Gabby’s stroller down a hallway with skylights in the ceiling. She looked down at Gabby and was shocked to see her eyes reacting to the sunlight. “I thought, ‘Well, you’re seeing that light!’” MaryMargret says. Gabby wasn’t blind, after all.

Despite the hardships, the couple decided they wanted more children. In 2007 MaryMargret had Anthony, and the following year she had Aleena. By this time, the Williamses had stopped trudging to specialists, accepting that Gabby was never going to be fixed. “At some point we just decided,” John recalls, “it’s time to make our peace.”

Mortal questions

When Walker began his scientific career, he focused on the female reproductive system as a model of “pure ageing”: a woman’s ovaries, even in the absence of any disease, slowly but inevitably slide into the throes of menopause. His studies investigated how food, light, hormones and brain chemicals influence fertility in rats. But academic science is slow. He hadn’t cured ageing by his 40th birthday, nor by his 50th or 60th. His life’s work was tangential, at best, to answering the question of why we’re mortal, and he wasn’t happy about it. He was running out of time.

So he went back to the drawing board. As he describes in his book, Why We Age, Walker began a series of thought experiments to reflect on what was known and not known about ageing.

Ageing is usually defined as the slow accumulation of damage in our cells, organs and tissues, ultimately causing the physical transformations that we all recognise in elderly people. Jaws shrink and gums recede. Skin slacks. Bones brittle, cartilage thins and joints swell. Arteries stiffen and clog. Hair greys. Vision dims. Memory fades. The notion that ageing is a natural, inevitable part of life is so fixed in our culture that we rarely question it. But biologists have been questioning it for a long time.

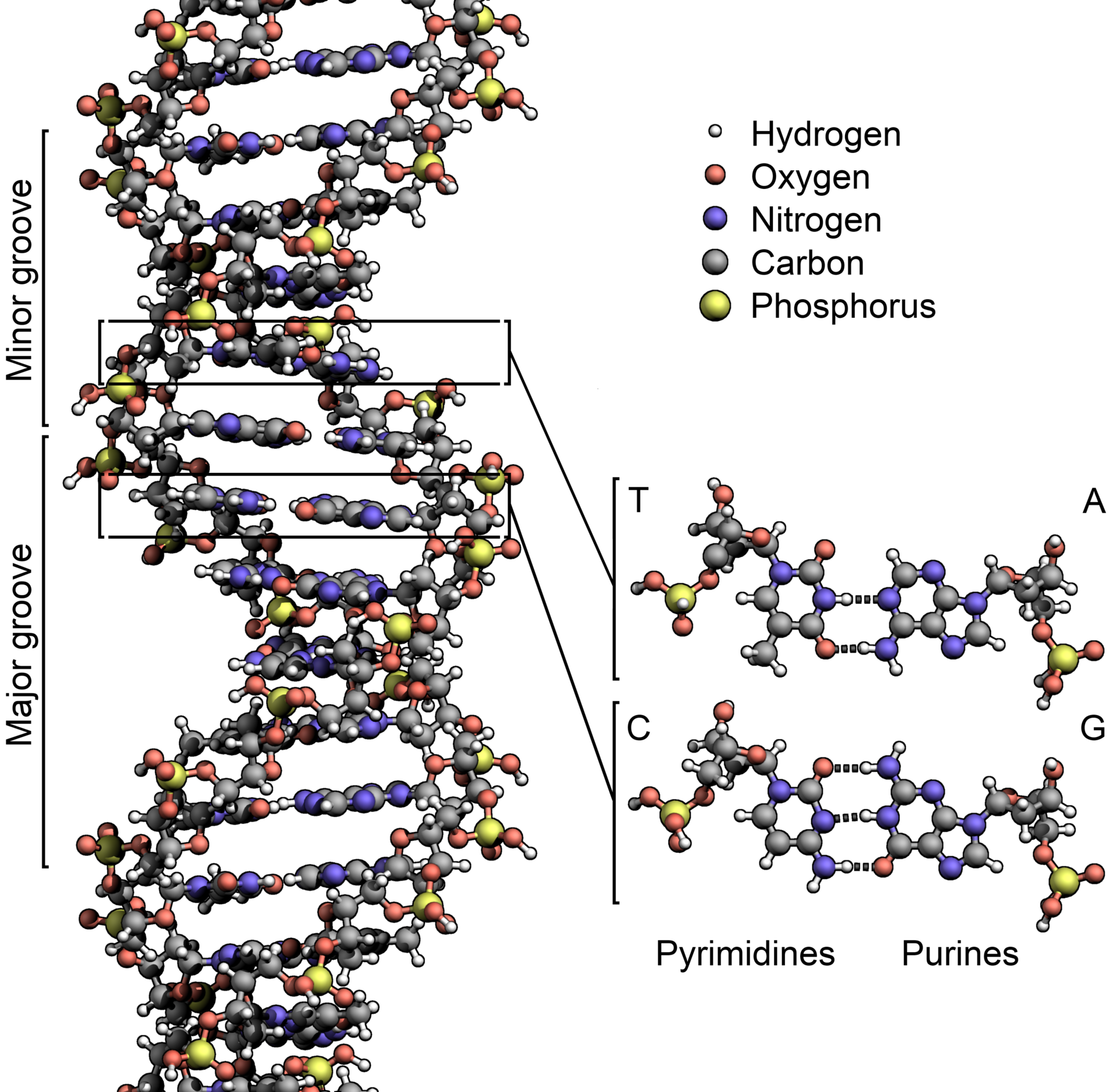

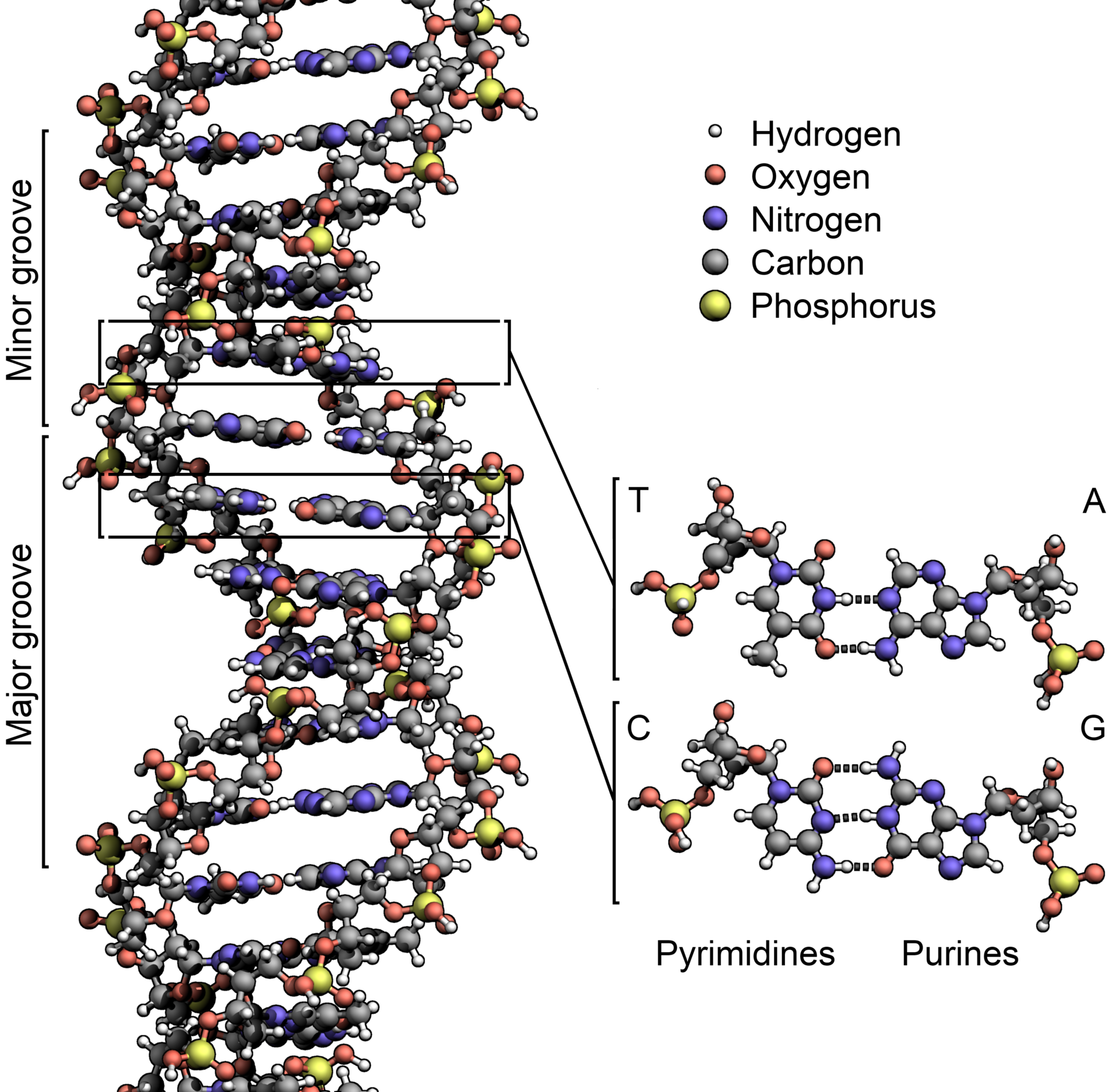

It’s a harsh world out there, and even young cells are vulnerable. It’s like buying a new car: the engine runs perfectly but is still at risk of getting smashed on the highway. Our young cells survive only because they have a slew of trusty mechanics on call. Take DNA, which provides the all-important instructions for making proteins. Every time a cell divides, it makes a near-perfect copy of its three-billion-letter code. Copying mistakes happen frequently along the way, but we have specialised repair enzymes to fix them, like an automatic spellcheck. Proteins, too, are ever vulnerable. If it gets too hot, they twist into deviant shapes that keep them from working. But here again, we have a fixer: so-called ‘heat shock proteins’ that rush to the aid of their misfolded brethren. Our bodies are also regularly exposed to environmental poisons, such as the reactive and unstable ‘free radical’ molecules that come from the oxidisation of the air we breathe. Happily, our tissues are stocked with antioxidants and vitamins that neutralise this chemical damage. Time and time again, our cellular mechanics come to the rescue.

Which leads to the biologists’ longstanding conundrum: if our bodies are so well tuned, why, then, does everything eventually go to hell?

One theory is that it all boils down to the pressures of evolution. Humans reproduce early in life, well before ageing rears its ugly head. All of the repair mechanisms that are important in youth – the DNA editors, the heat shock proteins, the antioxidants – help the young survive until reproduction, and are therefore passed down to future generations. But problems that show up after we’re done reproducing cannot be weeded out by evolution. Hence, ageing.

Most scientists say that ageing is not caused by any one culprit but by the breakdown of many systems at once. Our sturdy DNA mechanics become less effective with age, meaning that our genetic code sees a gradual increase in mutations. Telomeres, the sequences of DNA that act as protective caps on the ends of our chromosomes, get shorter every year. Epigenetic messages, which help turn genes on and off, get corrupted with time. Heat shock proteins run down, leading to tangled protein clumps that muck up the smooth workings of a cell. Faced with all of this damage, our cells try to adjust by changing the way they metabolise nutrients and store energy. To ward off cancer, they even know how to shut themselves down. But eventually cells stop dividing and stop communicating with each other, triggering the decline we see from the outside.

Scientists trying to slow the ageing process tend to focus on one of these interconnected pathways at a time. Some researchers have shown, for example, that mice on restricted-calorie diets live longer than normal. Other labs have reported that giving mice rapamycin, a drug that targets an important cell-growth pathway, boosts their lifespan. Still other groups are investigating substances that restore telomeres, DNA repair enzymes and heat shock proteins.

During his thought experiments, Walker wondered whether all of these scientists were fixating on the wrong thing. What if all of these various types of cellular damages were the consequences of ageing, but not the root cause of it? He came up with an alternative theory: that ageing is the unavoidable fallout of our development.

The idea sat on the back burner of Walker’s mind until the evening of 23 October 2005. He was working in his home office when his wife called out to him to join her in the family room. She knew he would want to see what was on TV: an episode of Dateline about a young girl who seemed to be “frozen in time”. Walker watched the show and couldn’t believe what he was seeing. Brooke Greenberg was 12 years old, but just 13 pounds (6kg) and 27 inches (69cm) long. Her doctors had never seen anything like her condition, and suspected the cause was a random genetic mutation. “She literally is the Fountain of Youth,” her father, Howard Greenberg, said.

Walker was immediately intrigued. He had heard of other genetic diseases, such as progeria and Werner syndrome, which cause premature ageing in children and adults respectively. But this girl seemed to be different. She had a genetic disease that stopped her development and with it, Walker suspected, the ageing process. Brooke Greenberg, in other words, could help him test his theory.

Uneven growth

Brooke was born a few weeks premature, with many birth defects. Her paediatrician labeled her with Syndrome X, not knowing what else to call it.

After watching the show, Walker tracked down Howard Greenberg’s address. Two weeks went by before Walker heard back, and after much discussion he was allowed to test Brooke. He was sent Brooke’s medical records as well as blood samples for genetic testing. In 2009, his team published a brief report describing her case.

Walker’s analysis found that Brooke’s organs and tissues were developing at different rates. Her mental age, according to standardised tests, was between one and eight months. Her teeth appeared to be eight years old; her bones, 10 years. She had lost all of her baby fat, and her hair and nails grew normally, but she had not reached puberty. Her telomeres were considerably shorter than those of healthy teenagers, suggesting that her cells were ageing at an accelerated rate.

All of this was evidence of what Walker dubbed “developmental disorganisation”. Brooke’s body seemed to be developing not as a coordinated unit, he wrote, but rather as a collection of individual, out-of-sync parts. “She is not simply ‘frozen in time’,” Walker wrote. “Her development is continuing, albeit in a disorganised fashion.”

The big question remained: why was Brooke developmentally disorganised? It wasn’t nutritional and it wasn’t hormonal. The answer had to be in her genes. Walker suspected that she carried a glitch in a gene (or a set of genes, or some kind of complex genetic programme) that directed healthy development. There must be some mechanism, after all, that allows us to develop from a single cell to a system of trillions of cells. This genetic programme, Walker reasoned, would have two main functions: it would initiate and drive dramatic changes throughout the organism, and it would also coordinate these changes into a cohesive unit.

Ageing, he thought, comes about because this developmental programme, this constant change, never turns off. From birth until puberty, change is crucial: we need it to grow and mature. After we’ve matured, however, our adult bodies don’t need change, but rather maintenance. “If you’ve built the perfect house, you would want to stop adding bricks at a certain point,” Walker says. “When you’ve built a perfect body, you’d want to stop screwing around with it. But that’s not how evolution works.” Because natural selection cannot influence traits that show up after we have passed on our genes, we never evolved a “stop switch” for development, Walker says. So we keep adding bricks to the house. At first this doesn’t cause much damage – a sagging roof here, a broken window there. But eventually the foundation can’t sustain the additions, and the house topples. This, Walker says, is ageing.

Brooke was special because she seemed to have been born with a stop switch. But finding the genetic culprit turned out to be difficult. Walker would need to sequence Brooke’s entire genome, letter by letter.

That never happened. Much to Walker’s chagrin, Howard Greenberg abruptly severed their relationship. The Greenbergs have not publicly explained why they ended their collaboration with Walker, and declined to comment for this article.

Second chance

In August 2009, MaryMargret Williams saw a photo of Brooke on the cover of People magazine, just below the headline “Heartbreaking mystery: The 16-year-old baby”. She thought Brooke sounded a lot like Gabby, so contacted Walker.

After reviewing Gabby’s details, Walker filled her in on his theory. Testing Gabby’s genes, he said, could help him in his mission to end age-related disease – and maybe even ageing itself.

This didn’t sit well with the Williamses. John, who works for the Montana Department of Corrections, often interacts with people facing the reality of our finite time on Earth. “If you’re spending the rest of your life in prison, you know, it makes you think about the mortality of life,” he says. What’s important is not how long you live, but rather what you do with the life you’re given. MaryMargret feels the same way. For years she has worked in a local dermatology office. She knows all too well the cultural pressures to stay young, and wishes more people would embrace the inevitability of getting older. “You get wrinkles, you get old, that’s part of the process,” she says.

But Walker’s research also had its upside. First and foremost, it could reveal whether the other Williams children were at risk of passing on Gabby’s condition.

For several months, John and MaryMargret hashed out the pros and cons. They were under no illusion that the fruits of Walker’s research would change Gabby’s condition, nor would they want it to. But they did want to know why. “What happened, genetically, to make her who she is?” John says. And more importantly: “Is there a bigger meaning for it?”

John and MaryMargret firmly believe that God gave them Gabby for a reason. Walker’s research offered them a comforting one: to help treat Alzheimer’s and other age-related diseases. “Is there a small piece that Gabby could present to help people solve these awful diseases?” John asks. “Thinking about it, it’s like, no, that’s for other people, that’s not for us.” But then he thinks back to the day Gabby was born. “I was in that delivery room, thinking the same thing – this happens to other people, not us.”

Still not entirely certain, the Williamses went ahead with the research.

Amassing evidence

Walker published his theory in 2011, but he’s only the latest of many researchers to think along the same lines. “Theories relating developmental processes to ageing have been around for a very long time, but have been somewhat under the radar for most researchers,” says Joao Pedro de Magalhaes, a biologist at the University of Liverpool. In 1932, for example, English zoologist George Parker Bidder suggested that mammals have some kind of biological “regulator” that stops growth after the animal reaches a specific size. Ageing, Bidder thought, was the continued action of this regulator after growth was done.

Subsequent studies showed that Bidder wasn’t quite right; there are lots of marine organisms, for example, that never stop growing but age anyway. Still, his fundamental idea of a developmental programme leading to ageing has persisted.

For several years, Stuart Kim’s group at Stanford University has been comparing which genes are expressed in young and old nematode worms. It turns out that some genes involved in ageing also help drive development in youth.

Kim suggested that the root cause of ageing is the “drift”, or mistiming, of developmental pathways during the ageing process, rather than an accumulation of cellular damage.

Other groups have since found similar patterns in mice and primates. One study, for example, found that many genes turned on in the brains of old monkeys and humans are the same as those expressed in young brains, suggesting that ageing and development are controlled by some of the same gene networks.

Perhaps most provocative of all, some studies of worms have shown that shutting down essential development genes in adults significantly prolongs life. “We’ve found quite a lot of genes in which this happened – several dozen,” de Magalhaes says.

Nobody knows whether the same sort of developmental-programme genes exist in people. But say that they do exist. If someone was born with a mutation that completely destroyed this programme, Walker reasoned, that person would undoubtedly die. But if a mutation only partially destroyed it, it might lead to a condition like what he saw in Brooke Greenberg or Gabby Williams. So if Walker could identify the genetic cause of Syndrome X, then he might also have a driver of the ageing process in the rest of us.

And if he found that, then could it lead to treatments that slow – or even end – ageing? “There’s no doubt about it,” he says.

Public stage

After agreeing to participate in Walker’s research, the Williamses, just like the Greenbergs before them, became famous. In January 2011, when Gabby was six, the television channel TLC featured her on a one-hour documentary. The Williams family also appeared on Japanese television and in dozens of newspaper and magazine articles.

Other than becoming a local celebrity, though, Gabby’s everyday life hasn’t changed much since getting involved in Walker’s research. She spends her days surrounded by her large family. She’ll usually lie on the floor, or in one of several cushions designed to keep her spine from twisting into a C shape. She makes noises that would make an outsider worry: grunting, gasping for air, grinding her teeth. Her siblings think nothing of it. They play boisterously in the same room, somehow always careful not to crash into her. Once a week, a teacher comes to the house to work with Gabby. She uses sounds and shapes on an iPad to try to teach cause and effect. When Gabby turned nine, last October, the family made her a birthday cake and had a party, just as they always do. Most of her gifts were blankets, stuffed animals and clothes, just as they are every year. Her aunt Jennie gave her make-up.

Walker teamed up with geneticists at Duke University and screened the genomes of Gabby, John and MaryMargret. This test looked at the exome, the 2% of the genome that codes for proteins. From this comparison, the researchers could tell that Gabby did not inherit any exome mutations from her parents – meaning that it wasn’t likely that her siblings would be able to pass on the condition to their kids. “It was a huge relief – huge,” MaryMargret says.

Still, the exome screening didn’t give any clues as to what was behind Gabby’s disease. Gabby carries several mutations in her exome, but none in a gene that would make sense of her condition. All of us have mutations littering our genomes. So it’s impossible to know, in any single individual, whether a particular mutation is harmful or benign – unless you can compare two people with the same condition.

All girls

Luckily for him, Walker’s continued presence in the media has led him to two other young girls who he believes have the same syndrome. One of them, Mackenzee Wittke, of Alberta, Canada, is now five years old, with has long and skinny limbs, just like Gabby. “We have basically been stuck in a time warp,” says her mother, Kim Wittke. The fact that all of these possible Syndrome X cases are girls is intriguing – it could mean that the crucial mutation is on their X chromosome. Or it could just be a coincidence.

Walker is working with a commercial outfit in California to compare all three girls’ entire genome sequences – the exome plus the other 98% of DNA code, which is thought to be responsible for regulating the expression of protein-coding genes.

For his theory, Walker says, “this is do or die – we’re going to do every single bit of DNA in these girls. If we find a mutation that’s common to them all, that would be very exciting.”

But that seems like a very big if.

Most researchers agree that finding out the genes behind Syndrome X is a worthwhile scientific endeavour, as these genes will no doubt be relevant to our understanding of development. They’re far less convinced, though, that the girls’ condition has anything to do with ageing. “It’s a tenuous interpretation to think that this is going to be relevant to ageing,” says David Gems, a geneticist at University College London. It’s not likely that these girls will even make it to adulthood, he says, let alone old age.

It’s also not at all clear that these girls have the same condition. Even if they do, and even if Walker and his collaborators discover the genetic cause, there would still be a steep hill to climb. The researchers would need to silence the same gene or genes in laboratory mice, which typically have a lifespan of two or three years. “If that animal lives to be 10, then we’ll know we’re on the right track,” Walker says. Then they’d have to find a way to achieve the same genetic silencing in people, whether with a drug or some kind of gene therapy. And then they’d have to begin long and expensive clinical trials to make sure that the treatment was safe and effective. Science is often too slow, and life too fast.

End of life

On 24 October 2013, Brooke passed away. She was 20 years old. MaryMargret heard about it when a friend called after reading it in a magazine. The news hit her hard. “Even though we’ve never met the family, they’ve just been such a part of our world,” she says.

MaryMargret doesn’t see Brooke as a template for Gabby – it’s not as if she now believes that she only has 11 years left with her daughter. But she can empathise with the pain the Greenbergs must be feeling. “It just makes me feel so sad for them, knowing that there’s a lot that goes into a child like that,” she says. “You’re prepared for them to die, but when it finally happens, you can just imagine the hurt.”

Today Gabby is doing well. MaryMargret and John are no longer planning her funeral. Instead, they’re beginning to think about what would happen if Gabby outlives them. (Sophia has offered to take care of her sister.) John turned 50 this year, and MaryMargret will be 41. If there were a pill to end ageing, they say they’d have no interest in it. Quite the contrary: they look forward to getting older, because it means experiencing the new joys, new pains and new ways to grow that come along with that stage of life.

Richard Walker, of course, has a fundamentally different view of growing old. When asked why he’s so tormented by it, he says it stems from childhood, when he watched his grandparents physically and psychologically deteriorate. “There was nothing charming to me about sedentary old people, rocking chairs, hot houses with Victorian trappings,” he says. At his grandparents’ funerals, he couldn’t help but notice that they didn’t look much different in death than they did at the end of life. And that was heartbreaking. “To say I love life is an understatement,” he says. “Life is the most beautiful and magic of all things.”

If his hypothesis is correct – who knows? – it might one day help prevent disease and modestly extend life for millions of people. Walker is all too aware, though, that it would come too late for him. As he writes in his book: “I feel a bit like Moses who, after wandering in the desert for most years of his life, was allowed to gaze upon the Promised Land but not granted entrance into it.”

Read the entire story here.

Story courtesy of BBC and Mosaic under Creative Commons License.

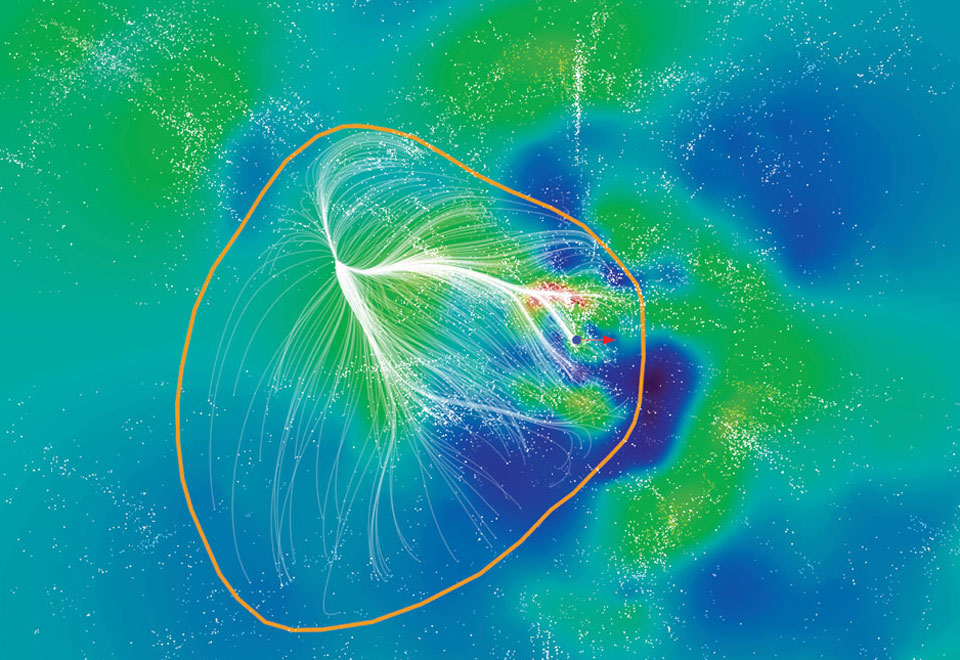

Image: DNA structure. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

It’s rather simple in theory, and only requires two steps. Step 1: Follow the lead of a city like Chattanooga, Tennessee. Step 2: Tell you monopolistic cable company what to do with its cables. Done. Now you have a 1 Gigabit Internet connection — around 50-100 times faster than your mother’s Wifi.

It’s rather simple in theory, and only requires two steps. Step 1: Follow the lead of a city like Chattanooga, Tennessee. Step 2: Tell you monopolistic cable company what to do with its cables. Done. Now you have a 1 Gigabit Internet connection — around 50-100 times faster than your mother’s Wifi.