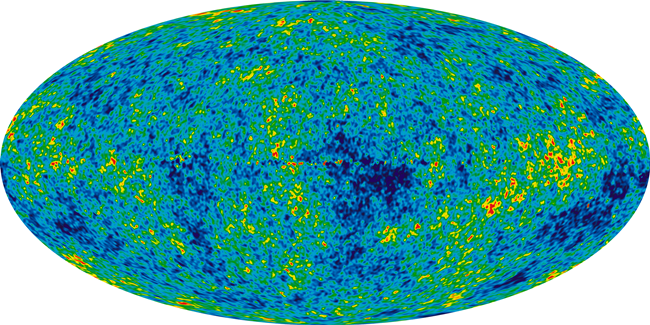

A recent study by Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London places the seat of our sense of beauty in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC). Not very romantic of course, but thoroughly reasonable that this compound emotion would be found in an area of the brain linked with reward and pleasure.

A recent study by Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London places the seat of our sense of beauty in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC). Not very romantic of course, but thoroughly reasonable that this compound emotion would be found in an area of the brain linked with reward and pleasure.

[div class=attrib]The results are described over at Not Exactly Rocket Science / Discover:[end-div]

Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London watched the brains of 21 volunteers as they looked at 30 paintings and listened to 30 musical excerpts. All the while, they were lying inside an fMRI scanner, a machine that measures blood flow to different parts of the brain and shows which are most active. The recruits rated each piece as “beautiful”, “indifferent” or “ugly”.

The scans showed that one part of their brains lit up more strongly when they experienced beautiful images or music than when they experienced ugly or indifferent ones – the medial orbitofrontal cortex or mOFC.

Several studies have linked the mOFC to beauty, but this is a sizeable part of the brain with many roles. It’s also involved in our emotions, our feelings of reward and pleasure, and our ability to make decisions. Nonetheless, Ishizu and Zeki found that one specific area, which they call “field A1” consistently lit up when people experienced beauty.

The images and music were accompanied by changes in other parts of the brain as well, but only the mOFC reacted to beauty in both forms. And the more beautiful the volunteers found their experiences, the more active their mOFCs were. That is not to say that the buzz of neurons in this area produces feelings of beauty; merely that the two go hand-in-hand.

Clearly, this is a great start, and as brain scientists get their hands on ever improving fMRI technology and other brain science tools our understanding will only get sharper. However, what still remains very much a puzzle is “why does our sense of beauty exist”?

The researchers go on to explain their results, albeit tentatively:

Our proposal shifts the definition of beauty very much in favour of the perceiving subject and away from the characteristics of the apprehended object. Our definition… is also indifferent to what is art and what is not art. Almost anything can be considered to be art, but only creations whose experience has, as a correlate, activity in mOFC would fall into the classification of beautiful art… A painting by Francis Bacon may be executed in a painterly style and have great artistic merit but may not qualify as beautiful to a subject, because the experience of viewing it does not correlate with activity in his or her mOFC.

In proposing this the researchers certainly seem to have hit on the underlying “how” of beauty, and it’s reliably consistent, though the sample was not large enough to warrant statistical significance. However, the researchers conclude that “A beautiful thing is met with the same neural changes in the brain of a wealthy cultured connoisseur as in the brain of a poor, uneducated novice, as long as both of them find it beautiful.”

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But why does beauty exist? What’s the point of marveling at a Rembrandt self portrait or a Bach fugue? To paraphrase Auden, beauty makes nothing happen. Unlike our more primal indulgences, the pleasure of perceiving beauty doesn’t ensure that we consume calories or procreate. Rather, the only thing beauty guarantees is that we’ll stare for too long at some lovely looking thing. Museums are not exactly adaptive.

The answer to this question has stumped the research community for quite some time, and will undoubtedly continue to do so for some time to come. Several recent cognitive research studies hint at possible answers related to reinforcement for curious and inquisitive behavior, reward for and feedback from anticipation responses, and pattern seeking behavior.

[div class=attrib]More from Jonah Lehrer for Wired:[end-div]

What I like about this speculation is that it begins to explain why the feeling of beauty is useful. The aesthetic emotion might have begun as a cognitive signal telling us to keep on looking, because there is a pattern here that we can figure out it. In other words, it’s a sort of a metacognitive hunch, a response to complexity that isn’t incomprehensible. Although we can’t quite decipher this sensation – and it doesn’t matter if the sensation is a painting or a symphony – the beauty keeps us from looking away, tickling those dopaminergic neurons and dorsal hairs. Like curiosity, beauty is a motivational force, an emotional reaction not to the perfect or the complete, but to the imperfect and incomplete. We know just enough to know that we want to know more; there is something here, we just don’t what. That’s why we call it beautiful.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Claude Monet, Water-Lily Pond and Weeping Willow. Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]First page of the manuscript of Bach’s lute suite in G Minor. Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

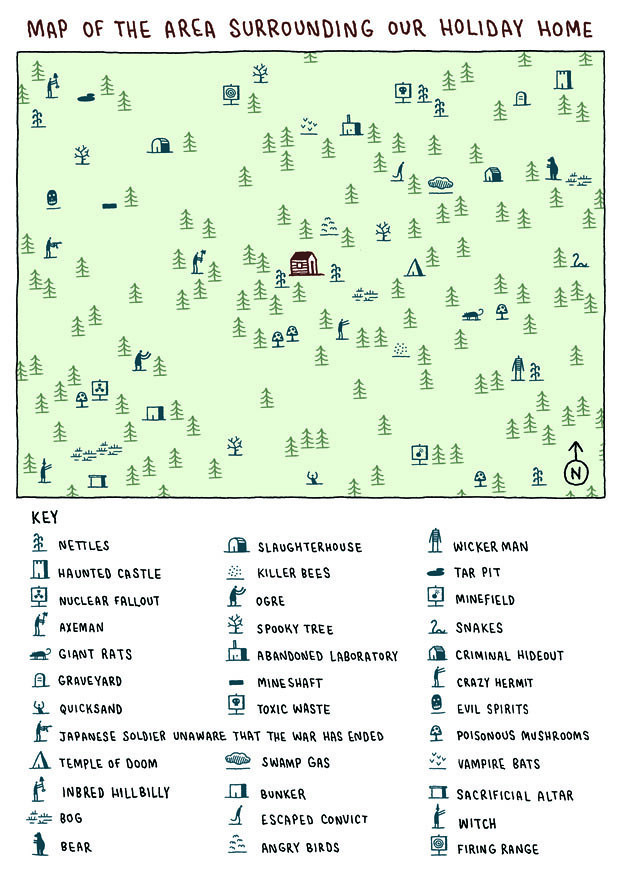

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs for Strange Maps:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Frank Jacobs for Strange Maps:[end-div]

Why do some words take hold in the public consciousness and persist through generations while others fall by the wayside after one season?

Why do some words take hold in the public consciousness and persist through generations while others fall by the wayside after one season? A poem by Billy Collins ushers in another week. Collins served two terms as the U.S. Poet Laureate, from 2001-2003. He is known for poetry imbued with leftfield humor and deep insight.

A poem by Billy Collins ushers in another week. Collins served two terms as the U.S. Poet Laureate, from 2001-2003. He is known for poetry imbued with leftfield humor and deep insight. Jonathan Ive, the design brains behind such iconic contraptions as the iMac, iPod and the iPhone discusses his notion of “undesign”. Ive has over 300 patents and is often cited as one of the most influential industrial designers of the last 20 years. Perhaps it’s purely coincidental that’s Ive’s understated “undesign” comes from his unassuming Britishness.

Jonathan Ive, the design brains behind such iconic contraptions as the iMac, iPod and the iPhone discusses his notion of “undesign”. Ive has over 300 patents and is often cited as one of the most influential industrial designers of the last 20 years. Perhaps it’s purely coincidental that’s Ive’s understated “undesign” comes from his unassuming Britishness.

Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope.

Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope. [div class=attrib]From Neuroanthropology:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Neuroanthropology:[end-div]

Scents are deeply evokative. A faint whiff of a distinct and rare scent can bring back a long forgotten memory and make it vivid, and do so like no other sense. Smells can make our stomachs churn and make us swoon.

Scents are deeply evokative. A faint whiff of a distinct and rare scent can bring back a long forgotten memory and make it vivid, and do so like no other sense. Smells can make our stomachs churn and make us swoon. A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom?

A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom? But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions: Skeptic

Skeptic Ushering in this week’s focus on the brain and the cognitive sciences is an Emily Dickinson poem.

Ushering in this week’s focus on the brain and the cognitive sciences is an Emily Dickinson poem.

Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.

Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.

[div class=attrib]From TreeHugger:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From TreeHugger:[end-div] That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

That very quaint form of communication, the printed postcard, reserved for independent children to their clingy parents and boastful travelers to their (not) distant (enough) family members, may soon become as arcane as the LP or paper-based map. Until the late-90s there were some rather common sights associated with the postcard: the tourist lounging in a cafe musing with great difficulty over the two or three pithy lines he would write from Paris; the traveler asking for a postcard stamp in broken German; the remaining 3 from a pack of 6 unwritten postcards of the Vatican now used as bookmarks; the over saturated colors of the sunset.

A poignant, poetic view of our relationships, increasingly mediated and recalled for us through technology. Conor O’Callaghan’s poem ushers in this week’s collection of articles at theDiagonal focused on technology.

A poignant, poetic view of our relationships, increasingly mediated and recalled for us through technology. Conor O’Callaghan’s poem ushers in this week’s collection of articles at theDiagonal focused on technology. Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

In 2007 UPS made the headlines by declaring left-hand turns for its army of delivery truck drivers undesirable. Of course, we left-handers have always known that our left or “

In 2007 UPS made the headlines by declaring left-hand turns for its army of delivery truck drivers undesirable. Of course, we left-handers have always known that our left or “

[div class=attrib]From Rolling Stone:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Rolling Stone:[end-div]