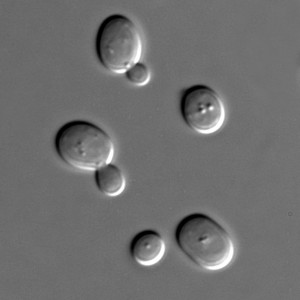

The world welcomed basic genetic engineering in the mid-1970s, when biotech pioneers Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen transferred DNA from one organism to another (bacteria). In so doing they created the first genetically modified organism (GMO). A mere forty years later we now have extremely powerful and accessible (cheap) biochemical tools for tinkering with the molecules of heredity. One of these tools, known as Crispr-Cas9, makes it easy and fast to move any genes around, within and across any species.

The technique promises immense progress in the fight against inherited illness, cancer treatment and viral infection. It also opens the door to untold manipulation of DNA in lower organisms and plants to develop an infection resistant and faster growing food supply, and to reimagine a whole host of biochemical and industrial processes (such as ethanol production).

Yet as is the case with many technological advances that hold great promise, tremendous peril lies ahead from this next revolution. Our bioengineering prowess has yet to be matched with a sound and pervasive ethical framework. Can humans reach a consensus on how to shape, focus and limit the application of such techniques? And, equally importantly, can we enforce these bioethical constraints before it’s too late to “uninvent” designer babies and bioweapons?

From Wired:

Spiny grass and scraggly pines creep amid the arts-and-crafts buildings of the Asilomar Conference Grounds, 100 acres of dune where California’s Monterey Peninsula hammerheads into the Pacific. It’s a rugged landscape, designed to inspire people to contemplate their evolving place on Earth. So it was natural that 140 scientists gathered here in 1975 for an unprecedented conference.

They were worried about what people called “recombinant DNA,” the manipulation of the source code of life. It had been just 22 years since James Watson, Francis Crick, and Rosalind Franklin described what DNA was—deoxyribonucleic acid, four different structures called bases stuck to a backbone of sugar and phosphate, in sequences thousands of bases long. DNA is what genes are made of, and genes are the basis of heredity.

Preeminent genetic researchers like David Baltimore, then at MIT, went to Asilomar to grapple with the implications of being able to decrypt and reorder genes. It was a God-like power—to plug genes from one living thing into another. Used wisely, it had the potential to save millions of lives. But the scientists also knew their creations might slip out of their control. They wanted to consider what ought to be off-limits.

By 1975, other fields of science—like physics—were subject to broad restrictions. Hardly anyone was allowed to work on atomic bombs, say. But biology was different. Biologists still let the winding road of research guide their steps. On occasion, regulatory bodies had acted retrospectively—after Nuremberg, Tuskegee, and the human radiation experiments, external enforcement entities had told biologists they weren’t allowed to do that bad thing again. Asilomar, though, was about establishing prospective guidelines, a remarkably open and forward-thinking move.

At the end of the meeting, Baltimore and four other molecular biologists stayed up all night writing a consensus statement. They laid out ways to isolate potentially dangerous experiments and determined that cloning or otherwise messing with dangerous pathogens should be off-limits. A few attendees fretted about the idea of modifications of the human “germ line”—changes that would be passed on from one generation to the next—but most thought that was so far off as to be unrealistic. Engineering microbes was hard enough. The rules the Asilomar scientists hoped biology would follow didn’t look much further ahead than ideas and proposals already on their desks.

Earlier this year, Baltimore joined 17 other researchers for another California conference, this one at the Carneros Inn in Napa Valley. “It was a feeling of déjà vu,” Baltimore says. There he was again, gathered with some of the smartest scientists on earth to talk about the implications of genome engineering.

The stakes, however, have changed. Everyone at the Napa meeting had access to a gene-editing technique called Crispr-Cas9. The first term is an acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” a description of the genetic basis of the method; Cas9 is the name of a protein that makes it work. Technical details aside, Crispr-Cas9 makes it easy, cheap, and fast to move genes around—any genes, in any living thing, from bacteria to people. “These are monumental moments in the history of biomedical research,” Baltimore says. “They don’t happen every day.”

Using the three-year-old technique, researchers have already reversed mutations that cause blindness, stopped cancer cells from multiplying, and made cells impervious to the virus that causes AIDS. Agronomists have rendered wheat invulnerable to killer fungi like powdery mildew, hinting at engineered staple crops that can feed a population of 9 billion on an ever-warmer planet. Bioengineers have used Crispr to alter the DNA of yeast so that it consumes plant matter and excretes ethanol, promising an end to reliance on petrochemicals. Startups devoted to Crispr have launched. International pharmaceutical and agricultural companies have spun up Crispr R&D. Two of the most powerful universities in the US are engaged in a vicious war over the basic patent. Depending on what kind of person you are, Crispr makes you see a gleaming world of the future, a Nobel medallion, or dollar signs.

The technique is revolutionary, and like all revolutions, it’s perilous. Crispr goes well beyond anything the Asilomar conference discussed. It could at last allow genetics researchers to conjure everything anyone has ever worried they would—designer babies, invasive mutants, species-specific bioweapons, and a dozen other apocalyptic sci-fi tropes. It brings with it all-new rules for the practice of research in the life sciences. But no one knows what the rules are—or who will be the first to break them.

In a way, humans were genetic engineers long before anyone knew what a gene was. They could give living things new traits—sweeter kernels of corn, flatter bulldog faces—through selective breeding. But it took time, and it didn’t always pan out. By the 1930s refining nature got faster. Scientists bombarded seeds and insect eggs with x-rays, causing mutations to scatter through genomes like shrapnel. If one of hundreds of irradiated plants or insects grew up with the traits scientists desired, they bred it and tossed the rest. That’s where red grapefruits came from, and most barley for modern beer.

Genome modification has become less of a crapshoot. In 2002, molecular biologists learned to delete or replace specific genes using enzymes called zinc-finger nucleases; the next-generation technique used enzymes named TALENs.

Yet the procedures were expensive and complicated. They only worked on organisms whose molecular innards had been thoroughly dissected—like mice or fruit flies. Genome engineers went on the hunt for something better.

As it happened, the people who found it weren’t genome engineers at all. They were basic researchers, trying to unravel the origin of life by sequencing the genomes of ancient bacteria and microbes called Archaea (as in archaic), descendants of the first life on Earth. Deep amid the bases, the As, Ts, Gs, and Cs that made up those DNA sequences, microbiologists noticed recurring segments that were the same back to front and front to back—palindromes. The researchers didn’t know what these segments did, but they knew they were weird. In a branding exercise only scientists could love, they named these clusters of repeating palindromes Crispr.

Then, in 2005, a microbiologist named Rodolphe Barrangou, working at a Danish food company called Danisco, spotted some of those same palindromic repeats in Streptococcus thermophilus, the bacteria that the company uses to make yogurt and cheese. Barrangou and his colleagues discovered that the unidentified stretches of DNA between Crispr’s palindromes matched sequences from viruses that had infected their S. thermophilus colonies. Like most living things, bacteria get attacked by viruses—in this case they’re called bacteriophages, or phages for short. Barrangou’s team went on to show that the segments served an important role in the bacteria’s defense against the phages, a sort of immunological memory. If a phage infected a microbe whose Crispr carried its fingerprint, the bacteria could recognize the phage and fight back. Barrangou and his colleagues realized they could save their company some money by selecting S. thermophilus species with Crispr sequences that resisted common dairy viruses.

As more researchers sequenced more bacteria, they found Crisprs again and again—half of all bacteria had them. Most Archaea did too. And even stranger, some of Crispr’s sequences didn’t encode the eventual manufacture of a protein, as is typical of a gene, but instead led to RNA—single-stranded genetic material. (DNA, of course, is double-stranded.)

That pointed to a new hypothesis. Most present-day animals and plants defend themselves against viruses with structures made out of RNA. So a few researchers started to wonder if Crispr was a primordial immune system. Among the people working on that idea was Jill Banfield, a geomicrobiologist at UC Berkeley, who had found Crispr sequences in microbes she collected from acidic, 110-degree water from the defunct Iron Mountain Mine in Shasta County, California. But to figure out if she was right, she needed help.

Luckily, one of the country’s best-known RNA experts, a biochemist named Jennifer Doudna, worked on the other side of campus in an office with a view of the Bay and San Francisco’s skyline. It certainly wasn’t what Doudna had imagined for herself as a girl growing up on the Big Island of Hawaii. She simply liked math and chemistry—an affinity that took her to Harvard and then to a postdoc at the University of Colorado. That’s where she made her initial important discoveries, revealing the three-dimensional structure of complex RNA molecules that could, like enzymes, catalyze chemical reactions.

The mine bacteria piqued Doudna’s curiosity, but when Doudna pried Crispr apart, she didn’t see anything to suggest the bacterial immune system was related to the one plants and animals use. Still, she thought the system might be adapted for diagnostic tests.

Banfield wasn’t the only person to ask Doudna for help with a Crispr project. In 2011, Doudna was at an American Society for Microbiology meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, when an intense, dark-haired French scientist asked her if she wouldn’t mind stepping outside the conference hall for a chat. This was Emmanuelle Charpentier, a microbiologist at Ume?a University in Sweden.

As they wandered through the alleyways of old San Juan, Charpentier explained that one of Crispr’s associated proteins, named Csn1, appeared to be extraordinary. It seemed to search for specific DNA sequences in viruses and cut them apart like a microscopic multitool. Charpentier asked Doudna to help her figure out how it worked. “Somehow the way she said it, I literally—I can almost feel it now—I had this chill down my back,” Doudna says. “When she said ‘the mysterious Csn1’ I just had this feeling, there is going to be something good here.”

Read the whole story here.