There was a time in the U.S. when the many would express shock and decry the verbal (or non-verbal) obscenity of the few. It was also easier for parents to shield the sensitive ears and eyes of their children from the infrequent obscenities of pop stars, politicians and others seeking the media spotlight.

Nowadays, we collectively yawn at the antics of the next post-pubescent alumnus of the Disney Channel. Our pop icons, politicians, news anchors and their ilk have made rudeness, vulgarity and narcissism the norm. Most of us no longer seem to be outraged — some are saddened, some are titillated — and then we shift our ever-decreasing attention spans to the next 15 minute teen-sensation. The vulgar and vain is now ever-present. So we become desensitized, and our public figures and wannabe stars seek the next even-bigger-thing to get themselves noticed before we look elsewhere.

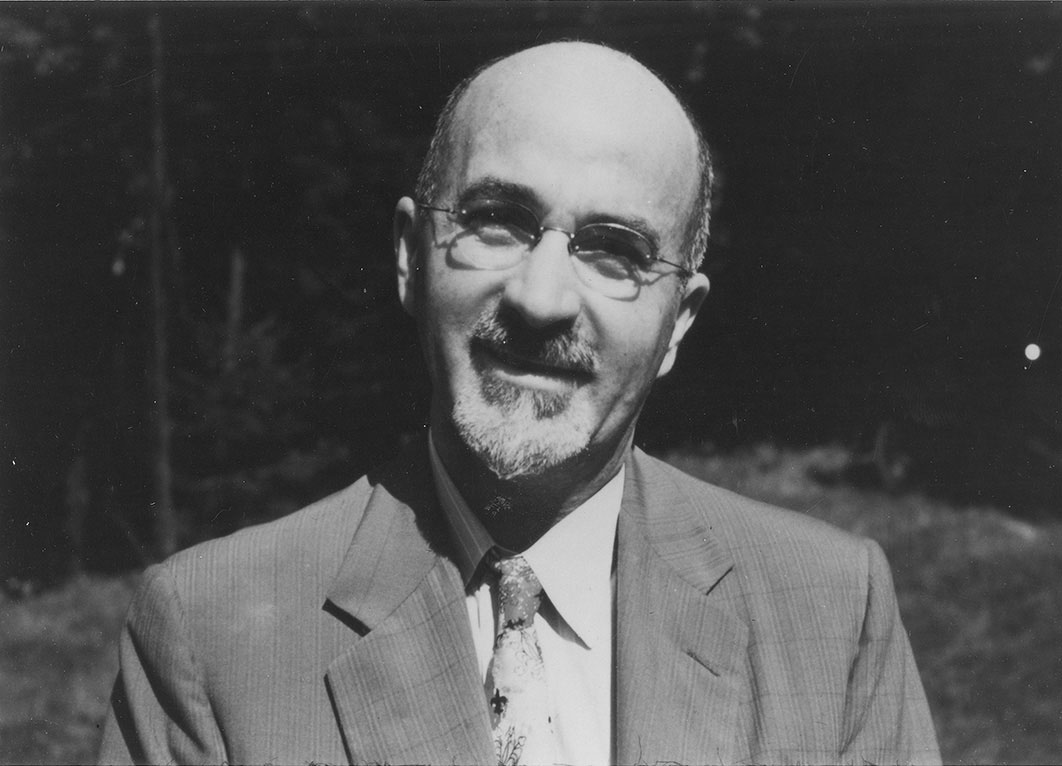

The essayist Lee Siegel seems to be on to something — many of our current obscenity-makers harken back to a time when their vulgarity actually conveyed meaning and could raise a degree of moral indignation in the audience. But now it’s just the new norm and a big yawn.

From Lee Siegel / WSJ:

“What’s celebrity sex, Dad?” It was my 7-year-old son, who had been looking over my shoulder at my computer screen. He mispronounced “celebrity” but spoke the word “sex” as if he had been using it all his life. “Celebrity six,” I said, abruptly closing my AOL screen. “It’s a game famous people play in teams of three,” I said, as I ushered him out of my office and downstairs into what I assumed was the safety of the living room.

No such luck. His 3-year-old sister had gotten her precocious little hands on my wife’s iPhone as it was charging on a table next to the sofa. By randomly tapping icons on the screen, she had conjured up an image of Beyoncé barely clad in black leather, caught in a suggestive pose that I hoped would suggest nothing at all to her or her brother.

And so it went on this typical weekend. The eff-word popped out of TV programs we thought were friendly enough to have on while the children played in the next room. Ads depicting all but naked couples beckoned to them from the mainstream magazines scattered around the house. The kids peered over my shoulder as I perused my email inbox, their curiosity piqued by the endless stream of solicitations having to do with one aspect or another of sex, sex, sex!

When did the culture become so coarse? It’s a question that quickly gets you branded as either an unsophisticated rube or some angry culture warrior. But I swear on my hard drive that I’m neither. My favorite movie is “Last Tango in Paris.” I agree (on a theoretical level) with the notorious rake James Goldsmith, who said that when a man marries his mistress, he creates a job vacancy. I once thought of writing a book-length homage to the eff-word in American culture, the apotheosis of which was probably Sir Ben Kingsley pronouncing it with several syllables in an episode of “The Sopranos.”

I’m cool, and I’m down with everything, you bet, but I miss a time when there were powerful imprecations instead of mere obscenity—or at least when sexual innuendo, because it was innuendo, served as a delicious release of tension between our private and public lives. Long before there was twerking, there were Elvis’s gyrations, which shocked people because gyrating hips are more associated with women (thrusting his hips forward would have had a masculine connotation). But Elvis’s physical motions on stage were all allusion, just as his lyrics were:

Touch it, pound it, what good does it do

There’s just no stoppin’ the way I feel for you

Cos’ every minute, every hour you’ll be shaken

By the strength and mighty power of my love

The relative subtlety stimulates the imagination, while casual obscenity drowns it out. And such allusiveness maintains social norms even as they are being violated—that’s sexy. The lyrics of Elvis’s “Power of My Love” gave him authority as a respected social figure, which made his asocial insinuations all the more gratifying.

The same went, in a later era, for the young Madonna : “Two by two their bodies become one.” It’s an electric image because you are actively engaged in completing it. Contrast that with the aging Madonna trash-talking like a kid:

Some girls got an attitude

Fake t— and a nasty mood

Hot s— when she’s in the nude

(In the naughty naked nude)

It’s the difference between locker-room talk and the language of seduction and desire. As Robbie Williams and the Pet Shop Boys observed a few years ago in their song “She’s Madonna”: “She’s got to be obscene to be believed.”

Everyone remembers the Rolling Stones’ “Brown Sugar,” whose sexual and racial provocations were perfectly calibrated for 1971. Few, if any, people can recall their foray into explicit obscenity two years later with “Star Star.” The earlier song was sly and licentious; behind the sexual allusions were the vitality and energy to carry them out. The explicitness of “Star Star” was for bored, weary, repressed squares in the suburbs, with their swingers parties and “key clubs.”

Just as religious vows of abstinence mean nothing without the temptations of desire—which is why St. Augustine spends so much time in his “Confessions” detailing the way he abandoned himself to the “fleshpots of Carthage”—violating a social norm when the social norm is absent yields no real pleasure. The great provocations are also great releases because they exist side by side with the prohibitions that they are provoking. Once you spell it all out, the tension between temptation and taboo disappears.

The open secret of violating a taboo with language that—through its richness, wit or rage—acknowledges the taboo is that it represents a kind of moralizing. In fact, all the magnificent potty mouths—from D.H. Lawrence to Norman Mailer, the Beats, the rockers, the proto-punks, punks and post-punks, Richard Pryor, Sam Kinison, Patti Smith, and up through, say, Sarah Silverman and the creators of “South Park”—have been moralizers. The late Lou Reed’s “I Wanna Be Black” is so full of racial slurs, obscenity and repugnant sexual imagery that I could not find one meaningful phrase to quote in this newspaper. It is also a wryly indignant song that rips into the racism of liberals whose reverence for black culture is a crippling caricature of black culture.

Though many of these vulgar outlaws were eventually warily embraced by the mainstream, to one degree or another, it wasn’t until long after their deaths that society assimilated them, still warily, and sometimes not at all. In their own lifetimes, they mostly existed on the margins or in the depths; you had to seek them out in society’s obscure corners. That was especially the case during the advent of new types of music. Swing, bebop, Sinatra, cool jazz, rock ‘n’ roll—all were specialized, youth-oriented upheavals in sound and style, and they drove the older generation crazy.

These days, with every new ripple in the culture transmitted, commented-on, analyzed, mocked, mashed-up and forgotten on countless universal devices every few minutes, everything is available to everyone instantly, every second, no matter how coarse or abrasive. You used to have to find your way to Lou Reed. Now as soon as some pointlessly vulgar song gets recorded, you hear it in a clothing store.

The shock value of earlier vulgarity partly lay in the fact that a hitherto suppressed impulse erupted into the public realm. Today Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram and the rest have made impulsiveness a new social norm. No one is driving anyone crazy with some new form of expression. You’re a parent and you don’t like it when Kanye West sings: “I sent this girl a picture of my d—. I don’t know what it is with females. But I’m not too good with that s—”? Shame on you.

The fact is that you’re hearing the same language, witnessing the same violence, experiencing the same graphic sexual imagery on cable, or satellite radio, or the Internet, or even on good old boring network TV, where almost explicit sexual innuendo and nakedly explicit violence come fast and furious. Old and young, high and low, the idiom is the same. Everything goes.

Graphic references to sex were once a way to empower the individual. The unfair boss, the dishonest general, the amoral politician might elevate themselves above other mortals and abuse their power, but everyone has a naked body and a sexual capacity with which to throw off balance the enforcers of some oppressive social norm. That is what Montaigne meant when he reminded his readers that “both kings and philosophers defecate.” Making public the permanent and leveling truths of our animal nature, through obscenity or evocations of sex, is one of democracy’s sacred energies. “Even on the highest throne in the world,” Montaigne writes, “we are still sitting on our asses.”

But we’ve lost the cleansing quality of “dirty” speech. Now it’s casual, boorish, smooth and corporate. Everybody is walking around sounding like Howard Stern. The trash-talking Jay-Z and Kanye West are superwealthy businessmen surrounded by bodyguards, media consultants and image-makers. It’s the same in other realms, too. What was once a cable revolution against treacly, morally simplistic network television has now become a formulaic ritual of “complex,” counterintuitive, heroic bad-guy characters like the murderous Walter White on “Breaking Bad” and the lovable serial killer in “Dexter.” And the constant stream of Internet gossip and brainless factoids passing themselves off as information has normalized the grossest references to sex and violence.

Back in the 1990s, growing explicitness and obscenity in popular culture gave rise to the so-called culture wars, in which the right and the left fought over the limits of free speech. Nowadays no one blames the culture for what the culture itself has become. This is, fundamentally, a positive development. Culture isn’t an autonomous condition that develops in isolation from other trends in society.

The JFK assassination, the bloody rampage of Charles Manson and his followers, the incredible violence of the Vietnam War—shocking history-in-the-making that was once hidden now became visible in American living rooms, night after night, through new technology, TV in particular. Culture raced to catch up with the straightforward transcriptions of current events.

And, of course, the tendency of the media, as old as Lord Northcliffe and the first mass-circulation newspapers, to attract business through sex and violence only accelerated. Normalized by TV and the rest of the media, the counterculture of the 1970s was smoothly assimilated into the commercial culture of the 1980s. Recall the 15-year-old Brooke Shields appearing in a commercial for Calvin Klein jeans in 1980, spreading her legs and saying, “Do you know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.” From then on, there was no going back.

Today, our cultural norms are driven in large part by technology, which in turn is often shaped by the lowest impulses in the culture. Behind the Internet’s success in making obscene images commonplace is the dirty little fact that it was the pornography industry that revolutionized the technology of the Internet. Streaming video, technology like Flash, sites that confirm the validity of credit cards were all innovations of the porn business. The Internet and pornography go together like, well, love and marriage. No wonder so much culture seems to aspire to porn’s depersonalization, absolute transparency and intolerance of secrets.

Read the entire article here.