Some theorists posit that we are living inside a simulation, that the entire universe is one giant, evolving model inside a grander reality. This is a fascinating idea, but may never be experimentally verifiable. So just relax — you and I may not be real, but we’ll never know.

On the other hand, but in a similar vein, researchers have themselves developed the broadest and most detailed simulation of the universe to date. Now, there are no “living” things yet inside this computer model, but it’s probably only a matter of time before our increasingly sophisticated simulations start wondering if they are simulations as well.

From the BBC:

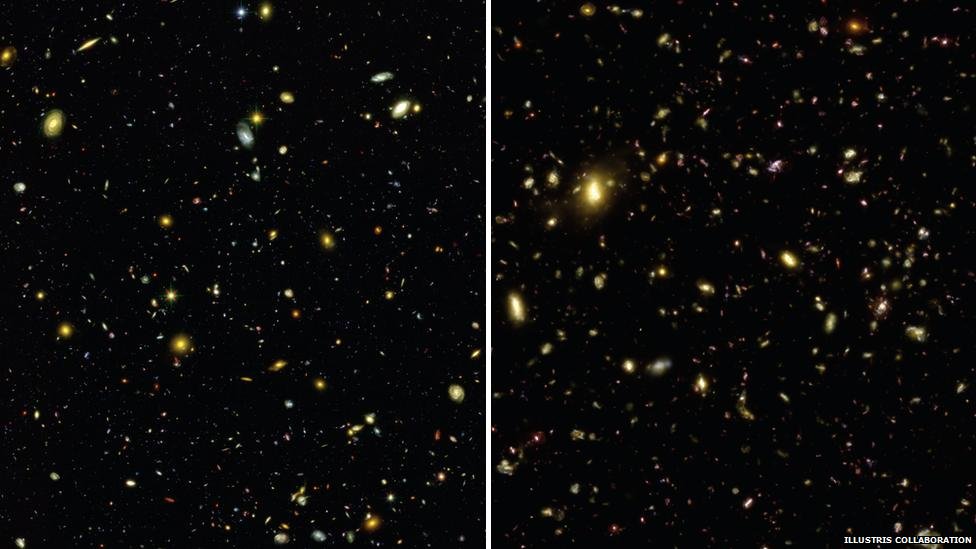

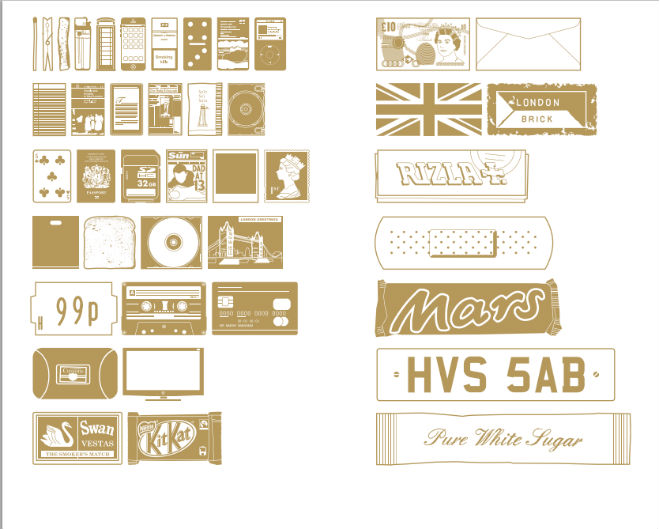

An international team of researchers has created the most complete visual simulation of how the Universe evolved.

The computer model shows how the first galaxies formed around clumps of a mysterious, invisible substance called dark matter.

It is the first time that the Universe has been modelled so extensively and to such great resolution.

The research has been published in the journal Nature.

Now we can get to grips with how stars and galaxies form and relate it to dark matter”

The simulation will provide a test bed for emerging theories of what the Universe is made of and what makes it tick.

One of the world’s leading authorities on galaxy formation, Professor Richard Ellis of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, described the simulation as “fabulous”.

“Now we can get to grips with how stars and galaxies form and relate it to dark matter,” he told BBC News.

The computer model draws on the theories of Professor Carlos Frenk of Durham University, UK, who said he was “pleased” that a computer model should come up with such a good result assuming that it began with dark matter.

“You can make stars and galaxies that look like the real thing. But it is the dark matter that is calling the shots”.

Cosmologists have been creating computer models of how the Universe evolved for more than 20 years. It involves entering details of what the Universe was like shortly after the Big Bang, developing a computer program which encapsulates the main theories of cosmology and then letting the programme run.

The simulated Universe that comes out at the other end is usually a very rough approximation of what astronomers really see.

The latest simulation, however, comes up with the Universe that is strikingly like the real one.

Immense computing power has been used to recreate this virtual Universe. It would take a normal laptop nearly 2,000 years to run the simulation. However, using state-of-the-art supercomputers and clever software called Arepo, researchers were able to crunch the numbers in three months.

Cosmic tree

In the beginning, it shows strands of mysterious material which cosmologists call “dark matter” sprawling across the emptiness of space like branches of a cosmic tree. As millions of years pass by, the dark matter clumps and concentrates to form seeds for the first galaxies.

Then emerges the non-dark matter, the stuff that will in time go on to make stars, planets and life emerge.

But early on there are a series of cataclysmic explosions when it gets sucked into black holes and then spat out: a chaotic period which was regulating the formation of stars and galaxies. Eventually, the simulation settles into a Universe that is similar to the one we see around us.

According to Dr Mark Vogelsberger of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who led the research, the simulations back many of the current theories of cosmology.

“Many of the simulated galaxies agree very well with the galaxies in the real Universe. It tells us that the basic understanding of how the Universe works must be correct and complete,” he said.

In particular, it backs the theory that dark matter is the scaffold on which the visible Universe is hanging.

“If you don’t include dark matter (in the simulation) it will not look like the real Universe,” Dr Vogelsberger told BBC News.

Read the entire article here.

Image: On the left: the real universe imaged via the Hubble telescope. On the right: a view of what emerges from the computer simulation. Courtesy of BBC / Illustris Collaboration.