While the revelations about the National Security Agency (NSA) snooping on private communications of U.S. citizens are extremely troubling, the situation could be much worse. Cast a sympathetic thought to the Her Majesty’s subjects in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Island, where almost everyone eavesdrops on everyone else. While the island nation of 60 million covers roughly the same area as Michigan, it is swathed in over 4 million CCTV (closed circuit television) surveillance cameras.

From Slate:

We adore the English here in the States. They’re just so precious! They call traffic circles “roundabouts,” prostitutes “prozzies,” and they have a queen. They’re ever so polite and carry themselves with such admirable poise. We love their accents so much, we use them in historical films to give them a bit more gravitas. (Just watch The Last Temptation of Christ to see what happens when we don’t: Judas doesn’t sound very intimidating with a Brooklyn accent.)

What’s not so cute is the surveillance society they’ve built—but the U.S. government seems pretty enamored with it.

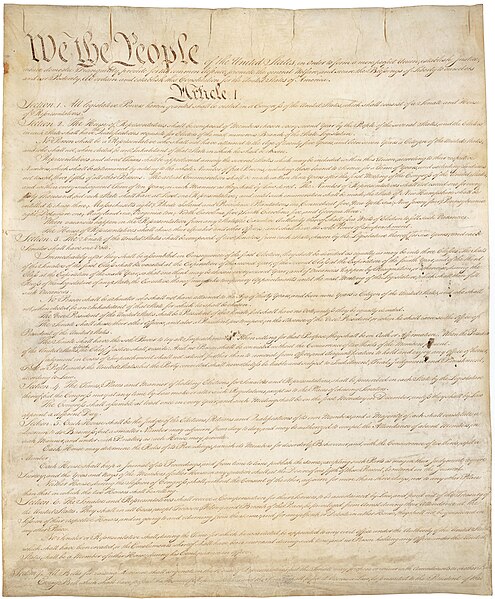

The United Kingdom is home to an intense surveillance system. Most of the legal framework for this comes from the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which dates all the way back to the year 2000. RIPA is meant to support criminal investigation, preventing disorder, public safety, public health, and, of course, “national security.” If this extremely broad application of law seems familiar, it should: The United States’ own PATRIOT Act is remarkably similar in scope and application. Why should the United Kingdom have the best toys, after all?

This is one of the problems with being the United Kingdom’s younger sibling. We always want what Big Brother has. Unless it’s soccer. Wiretaps, though? We just can’t get enough!

The PATRIOT Act, broad as it is, doesn’t match RIPA’s incredible wiretap allowances. In 1994, the United States passed the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act, which mandated that service providers give the government “technical assistance” in the use of wiretaps. RIPA goes a step further and insists that wiretap capability be implemented right into the system. If you’re a service provider and can’t set up plug-and-play wiretap capability within a short time, Johnny English comes knocking at your door to say, ” ‘Allo, guvna! I ‘ear tell you ‘aven’t put in me wiretaps yet. Blimey! We’ll jus’ ‘ave to give you a hefty fine! Ods bodkins!” Wouldn’t that be awful (the law, not the accent)? It would, and it’s just what the FBI is hoping for. CALEA is getting a rewrite that, if it passes, would give the FBI that very capability.

I understand. Older siblings always get the new toys, and it’s only natural that we want to have them as well. But why does it have to be legal toys for surveillance? Why can’t it be chocolate? The United Kingdom enjoys chocolate that’s almost twice as good as American chocolate. Literally, they get 20 percent solid cocoa in their chocolate bars, while we suffer with a measly 11 percent. Instead, we’re learning to shut off the Internet for entire families.

That’s right. In the United Kingdom, if you are just suspected of having downloaded illegally obtained material three times (it’s known as the “three strikes” law), your Internet is cut off. Not just for you, but for your entire household. Life without the Internet, let’s face it, sucks. You’re not just missing out on videos of cats falling into bathtubs. You’re missing out of communication, jobs, and being a 21st-century citizen. Maybe this is OK in the United Kingdom because you can move up north, become a farmer, and enjoy a few pints down at the pub every night. Or you can just get a new ISP, because the United Kingdom actually has a competitive market for ISPs. The United States, as an homage, has developed the so-called “copyright alert system.” It works much the same way as the U.K. law, but it provides for six “strikes” instead of three and has a limited appeals system, in which the burden of proof lies on the suspected customer. In the United States, though, the rights-holders monitor users for suspected copyright infringement on their own, without the aid of ISPs. So far, we haven’t adopted the U.K. system in which ISPs are expected to monitor traffic and dole out their three strikes at their discretion.

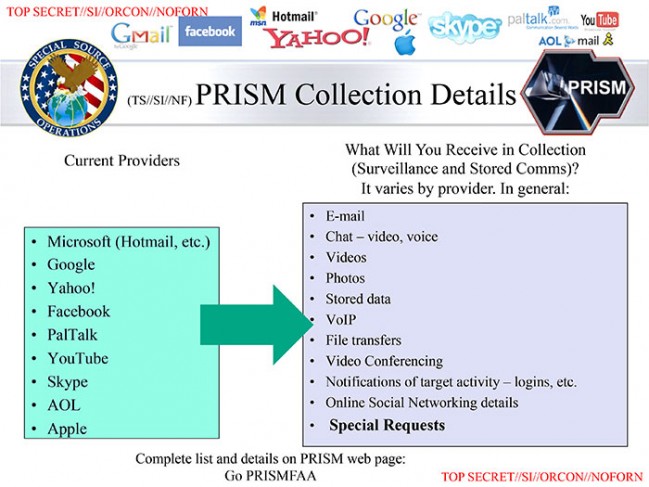

These are examples of more targeted surveillance of criminal activities, though. What about untargeted mass surveillance? On June 21, one of Edward Snowden’s leaks revealed that the Government Communications Headquarters, the United Kingdom’s NSA equivalent, has been engaging in a staggering amount of data collection from civilians. This development generated far less fanfare than the NSA news, perhaps because the legal framework for this data collection has existed for a very long time under RIPA, and we expect surveillance in the United Kingdom. (Or maybe Americans were just living down to the stereotype of not caring about other countries.) The NSA models follow the GCHQ’s very closely, though, right down to the oversight, or lack thereof.

Media have labeled the FISA court that regulates the NSA’s surveillance as a “rubber-stamp” court, but it’s no match for the omnipotence of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, which manages oversight for MI5, MI6, and the GCHQ. The Investigatory Powers Tribunal is exempt from the United Kingdom’s Freedom of Information Act, so it doesn’t have to share a thing about its activities (FISA apparently does not have this luxury—yet). On top of that, members of the tribunal are appointed by the queen. The queen. The one with the crown who has jubilees and a castle and probably a court wizard. Out of 956 complaints to the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, five have been upheld. Now that’s a rubber-stamp court we can aspire to!

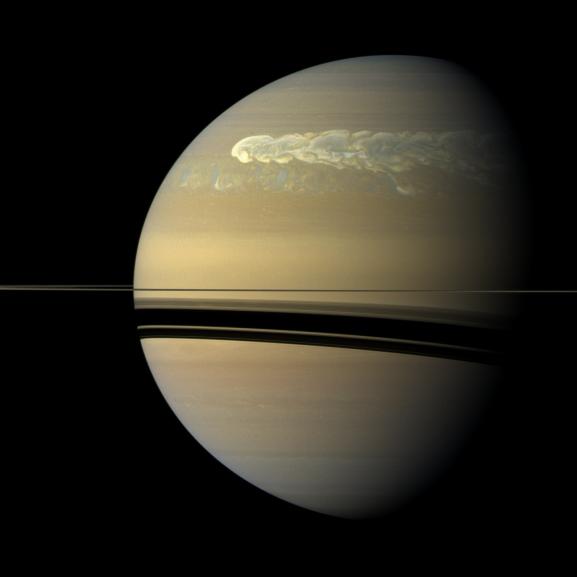

Or perhaps not. The future of U.S. surveillance looks very grim if we’re set on following the U.K.’s lead. Across the United Kingdom, an estimated 4.2 million CCTV cameras, some with facial-recognition capability, keep watch on nearly the entire nation. (This can lead to some Monty Python-esque high jinks.) Washington, D.C., took its first step toward strong camera surveillance in 2008, when several thousand were installed ahead of President Obama’s inauguration.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Royal coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, as used in England and Wales, and Scotland. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Have you ever taken a date to a cerebral movie or the opera? Have you ever taken a classic work of literature to read at the beach? If so, you are not alone. But why are you doing it?

Have you ever taken a date to a cerebral movie or the opera? Have you ever taken a classic work of literature to read at the beach? If so, you are not alone. But why are you doing it?

There is no doubting that technology’s grasp finds us at increasingly younger ages. No longer is it just our teens constantly mesmerized by status updates on their mobiles, and not just our “in-betweeners” addicted to “facetiming” with their BFFs. Now our technologies are fast becoming the tools of choice for our kindergarteners and pre-K kids. Some parents lament.

There is no doubting that technology’s grasp finds us at increasingly younger ages. No longer is it just our teens constantly mesmerized by status updates on their mobiles, and not just our “in-betweeners” addicted to “facetiming” with their BFFs. Now our technologies are fast becoming the tools of choice for our kindergarteners and pre-K kids. Some parents lament. Technology is altering the lives of us all. Often it is a positive influence, offering its users tremendous benefits from time-saving to life-extension. However, the relationship of technology to our employment is more complex and usually detrimental.

Technology is altering the lives of us all. Often it is a positive influence, offering its users tremendous benefits from time-saving to life-extension. However, the relationship of technology to our employment is more complex and usually detrimental. The world of fiction is populated with hundreds of different genres — most of which were invented by clever marketeers anxious to ensure vampire novels (teen / horror) don’t live next to classic works (literary) on real or imagined (think Amazon) book shelves. So, it should come as no surprise to see a new category recently emerge: cli-fi.

The world of fiction is populated with hundreds of different genres — most of which were invented by clever marketeers anxious to ensure vampire novels (teen / horror) don’t live next to classic works (literary) on real or imagined (think Amazon) book shelves. So, it should come as no surprise to see a new category recently emerge: cli-fi. Research shows how children as young as four years empathize with some but not others. It’s all about the group: which peer group you belong to versus the rest. Thus, the uphill struggle to instill tolerance in the next generation needs to begin very early in life.

Research shows how children as young as four years empathize with some but not others. It’s all about the group: which peer group you belong to versus the rest. Thus, the uphill struggle to instill tolerance in the next generation needs to begin very early in life.

Soon courtesy of Amazon, Google and other retail giants, and of course lubricated by the likes of the ubiquitous UPS and Fedex trucks, you may be able to dispense with the weekly or even daily trip to the grocery store. Amazon is expanding a trial of its same-day grocery delivery service, and others are following suit in select local and regional tests.

Soon courtesy of Amazon, Google and other retail giants, and of course lubricated by the likes of the ubiquitous UPS and Fedex trucks, you may be able to dispense with the weekly or even daily trip to the grocery store. Amazon is expanding a trial of its same-day grocery delivery service, and others are following suit in select local and regional tests. Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence?

Professor of Philosophy Gregory Currie tackles a thorny issue in his latest article. The question he seeks to answer is, “does great literature make us better?” It’s highly likely that a poll of most nations would show the majority of people believe that literature does in fact propel us in a forward direction, intellectually, morally, emotionally and culturally. It seem like a no-brainer. But where is the hard evidence?

The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction.

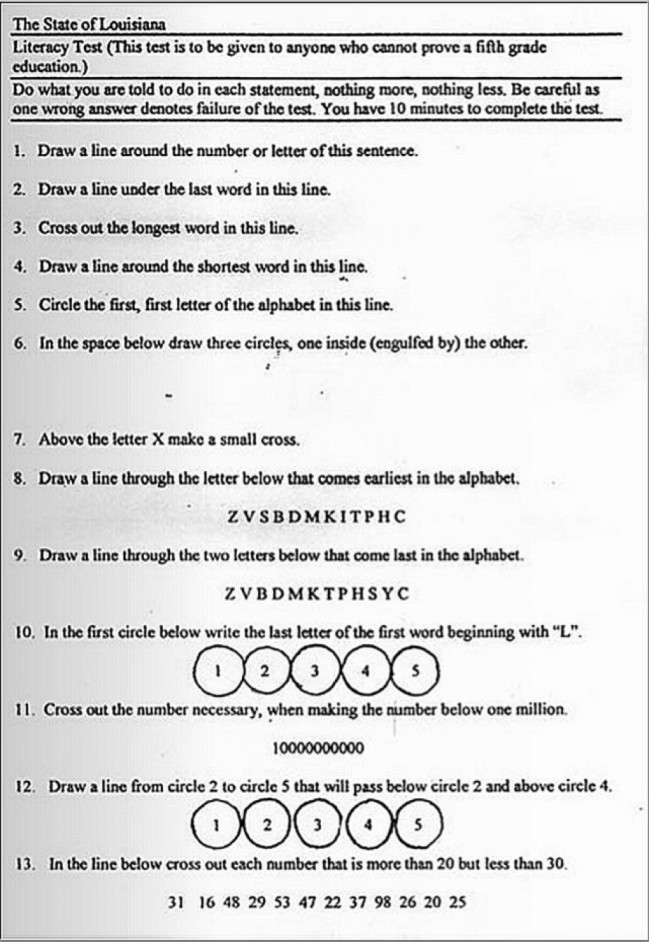

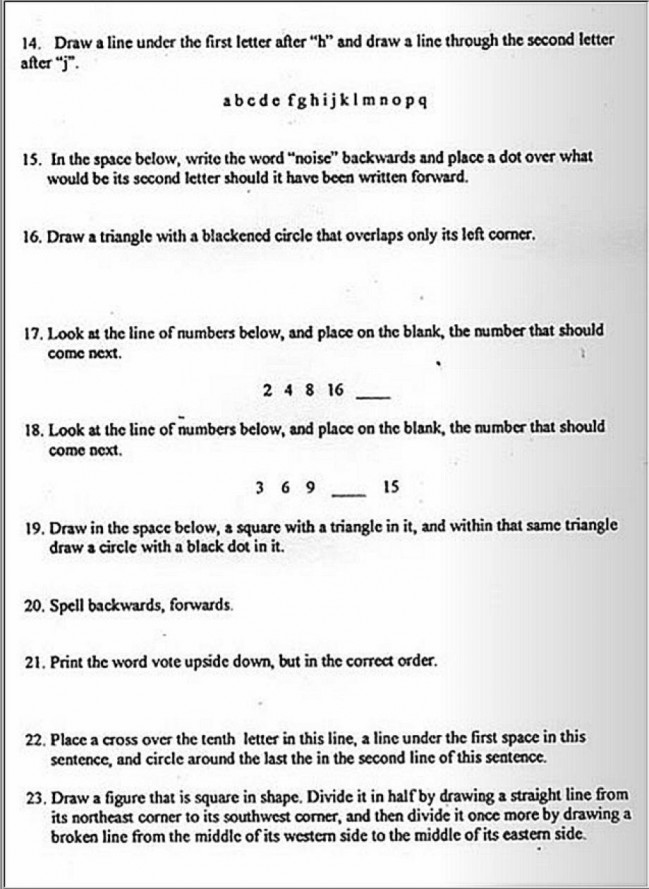

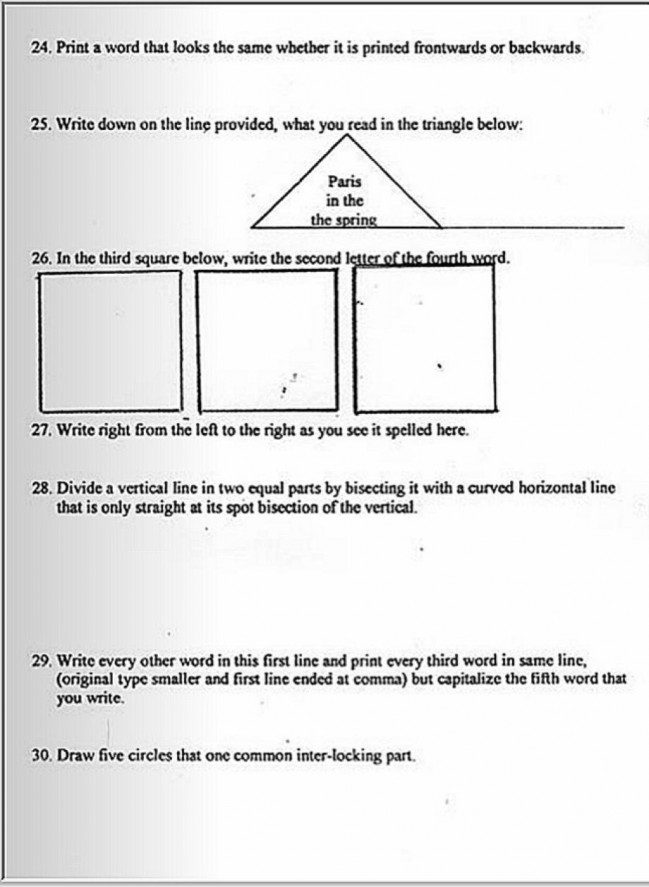

The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction. Paradoxically the law and common sense often seem to be at odds. Justice may still be blind, at least in most open democracies, but there seems to be no question as to the stupidity of much of our law.

Paradoxically the law and common sense often seem to be at odds. Justice may still be blind, at least in most open democracies, but there seems to be no question as to the stupidity of much of our law. It is strange to see the reaction to a remarkable disclosure such as that by the leaker / whistleblower Edward Snowden about the National Security Agency (NSA) peering into all our daily, digital lives. One strange reaction comes from the political left: the left desires a broad and activist government, ready to protect us all, but decries the NSA’s snooping. Another odd reaction comes from the political right: the right wants government out of people’s lives, but yet embraces the idea that the NSA should be looking for virtual skeletons inside people’s digital closets.

It is strange to see the reaction to a remarkable disclosure such as that by the leaker / whistleblower Edward Snowden about the National Security Agency (NSA) peering into all our daily, digital lives. One strange reaction comes from the political left: the left desires a broad and activist government, ready to protect us all, but decries the NSA’s snooping. Another odd reaction comes from the political right: the right wants government out of people’s lives, but yet embraces the idea that the NSA should be looking for virtual skeletons inside people’s digital closets. It’s safe to suggest that most of us above a certain age — let’s say 30 — wish to stay young. It is also safer to suggest, in the absence of a solution to this first wish, that many of us wish to age gracefully and happily. Yet for most of us, especially in the West, we age in a less dignified manner in combination with colorful medicines, lengthy tubes, and unpronounceable procedures. We are collectively living longer. But, the quality of those extra years leaves much to be desired.

It’s safe to suggest that most of us above a certain age — let’s say 30 — wish to stay young. It is also safer to suggest, in the absence of a solution to this first wish, that many of us wish to age gracefully and happily. Yet for most of us, especially in the West, we age in a less dignified manner in combination with colorful medicines, lengthy tubes, and unpronounceable procedures. We are collectively living longer. But, the quality of those extra years leaves much to be desired. On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great.

On June 9, 2013 we lost Iain Banks to cancer. He was a passionate human(ist) and a literary great.