Ayn Rand: anti-collectivist ideologue, standard-bearer for unapologetic individualism and rugged self-reliance, or selfish, fantasist and elitist hypocrite?

Ayn Rand: anti-collectivist ideologue, standard-bearer for unapologetic individualism and rugged self-reliance, or selfish, fantasist and elitist hypocrite?

Political conservatives and libertarians increasingly flock to her writings and support her philosophy of individualism and unfettered capitalism, which she dubbed, “objectivism”. On the other hand, liberals see her as selfish zealot, elitist, narcissistic, even psychopathic.

The truth, of course, is more nuanced and complex, especially the private Ayn Rand versus the very public persona. Thus those who fail to delve into Rand’s traumatic and colorful history fail to grasp the many paradoxes and contradictions that she enshrined.

Rand was firmly and vociferously pro-choice, yet she believed that women should submit to the will of great men. She was a devout atheist and outspoken pacifist, yet she believed Native Americans fully deserved their cultural genocide for not grasping capitalism. She viewed homosexuality as disgusting and immoral, but supported non-discrimination protection for homosexuals in the public domain, yet opposed such rights in private, all the while having an extremely colorful private life herself. She was a valiant opponent of government and federal regulation in all forms. Publicly, she viewed Social Security, Medicare and other “big government” programs with utter disdain, their dependents nothing more than weak-minded loafers and “takers”. Privately, later in life, she accepted payments from Social Security and Medicare. Perhaps most paradoxically, Rand derided those who would fake their own reality, while at the same time being chronically dependent on mind-distorting amphetamines; popping speed at the same time as writing her keystones to objectivism: Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

As an atheist Ayn Rand did not approve of shrines but the hushed, air-conditioned headquarters which bears her name acts as a secular version. Her walnut desk occupies a position of honour. She smiles from a gallery of black and white photos, young in some, old in others. A bronze bust, larger than life, tilts her head upward, jaw clenched, expression resolute.

The Ayn Rand Institute in Irvine, California, venerates the late philosopher as a prophet of unfettered capitalism who showed America the way. A decade ago it struggled to have its voice heard. Today its message booms all the way to Washington DC.

It was a transformation which counted Paul Ryan, chairman of the House budget committee, as a devotee. He gave Rand’s novel, Atlas Shrugged, as Christmas presents and hailed her as “the reason I got into public service”.

Then, last week, he was selected as the Republican vice-presidential nominee and his enthusiasm seemed to evaporate. In fact, the backtracking began earlier this year when Ryan said as a Catholic his inspiration was not Rand’s “objectivism” philosophy but Thomas Aquinas’.

The flap has illustrated an acute dilemma for the institute. Once peripheral, it has veered close to mainstream, garnering unprecedented influence. The Tea Party has adopted Rand as a seer and waves placards saying “We should shrug” and “Going Galt”, a reference to an Atlas Shrugged character named John Galt.

Prominent Republicans channel Rand’s arguments in promises to slash taxes and spending and to roll back government. But, like Ryan, many publicly renounce the controversial Russian emigre as a serious influence. Where, then, does that leave the institute, the keeper of her flame?

Given Rand’s association with plutocrats – she depicted captains of industry as “producers” besieged by parasitic “moochers” – the headquarters are unexpectedly modest. Founded in 1985 three years after Rand’s death, the institution moved in 2002 from Marina del Rey, west of Los Angeles, to a drab industrial park in Irvine, 90 minutes south, largely to save money. It shares a nondescript two-storey building with financial services and engineering companies.

There is little hint of Galt, the character who symbolises the power and glory of the human mind, in the bland corporate furnishings. But the quotations and excerpts adorning the walls echo a mission which drove Rand and continues to inspire followers as an urgent injunction.

“The demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest.”

These, said Onkar Ghate, the institute’s vice-president, are relatively good times for Randians. “Our primary mission is to advance awareness of her ideas and promote her philosophy. I must say, it’s going very well.”

On that point, if none other, conservatives and progressives may agree. Thirty years after her death Rand, as a radical intellectual and political force, is going very well indeed. Her novel Atlas Shrugged, a 1,000 page assault on big government, social welfare and altruism first published in 1957, is reportedly selling more than 400,000 copies per year and is being made into a movie trilogy. Its radical author, who also penned The Fountainhead and other novels and essays, is the subject of a recent documentary and spate of books.

To critics who consider Rand’s philosophy that “of the psychopath, a misanthropic fantasy of cruelty, revenge and greed”, her posthumous success is alarming.

Relatively little attention however has been paid to the institute which bears her name and works, often behind the scenes, to direct her legacy and shape right-wing debate.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

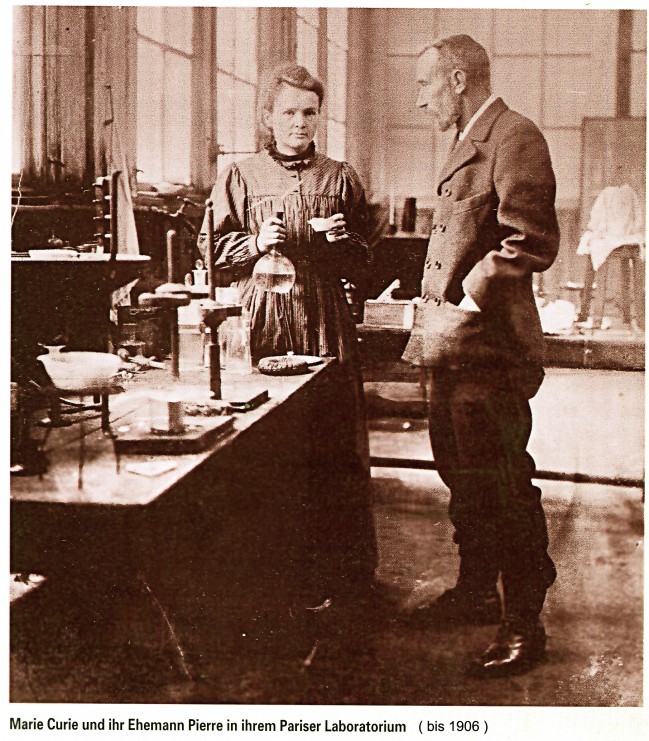

[div class=attrib]Image: Ayn Rand in 1957. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]

We excerpt an fascinating article from I09 on the association of science fiction to philosophical inquiry. It’s quiet remarkable that this genre of literature can provide such a rich vein for philosophers to mine, often more so than reality itself. Though, it is no coincidence that our greatest authors of science fiction were, and are, amateur philosophers at heart.

We excerpt an fascinating article from I09 on the association of science fiction to philosophical inquiry. It’s quiet remarkable that this genre of literature can provide such a rich vein for philosophers to mine, often more so than reality itself. Though, it is no coincidence that our greatest authors of science fiction were, and are, amateur philosophers at heart.

There is no doubt that online reviews for products and services, from books to news cars to a vacation spot, have revolutionized shopping behavior. Internet and mobile technology has made gathering, reviewing and publishing open and honest crowdsourced opinion simple, efficient and ubiquitous.

There is no doubt that online reviews for products and services, from books to news cars to a vacation spot, have revolutionized shopping behavior. Internet and mobile technology has made gathering, reviewing and publishing open and honest crowdsourced opinion simple, efficient and ubiquitous.

A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague.

A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague. Robert J. Samuelson paints a sobering picture of the once credible and seemingly attainable American Dream — the generational progress of upward mobility is no longer a given. He is the author of “The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence”.

Robert J. Samuelson paints a sobering picture of the once credible and seemingly attainable American Dream — the generational progress of upward mobility is no longer a given. He is the author of “The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence”. The United States is gripped by political deadlock. The Do-Nothing Congress consistently gets lower approval ratings than our banks, Paris Hilton, lawyers and BP during the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico. This stasis is driven by seemingly intractable ideological beliefs and a no-compromise attitude from both the left and right sides of the aisle.

The United States is gripped by political deadlock. The Do-Nothing Congress consistently gets lower approval ratings than our banks, Paris Hilton, lawyers and BP during the catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico. This stasis is driven by seemingly intractable ideological beliefs and a no-compromise attitude from both the left and right sides of the aisle.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

Ex-Facebook employee number 51, gives us a glimpse from within the social network giant. It’s a tale of social isolation, shallow relationships, voyeurism, and narcissistic performance art. It’s also a tale of the re-discovery of life prior to “likes”, “status updates”, “tweets” and “followers”.

The United States is often cited as the most generous nation on Earth. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most violent, having one of the highest murder rates of any industrialized country. Why this tragic paradox?

The United States is often cited as the most generous nation on Earth. Unfortunately, it is also one of the most violent, having one of the highest murder rates of any industrialized country. Why this tragic paradox? Hot from the TechnoSensual Exposition in Vienna, Austria, come clothes that can be made transparent or opaque, and clothes that can detect a wearer telling a lie. While the value of the former may seem dubious outside of the home, the latter invention should be a mandatory garment for all politicians and bankers. Or, for the less adventurous, millinery fashionistas, how about a hat that reacts to ambient radio waves?

Hot from the TechnoSensual Exposition in Vienna, Austria, come clothes that can be made transparent or opaque, and clothes that can detect a wearer telling a lie. While the value of the former may seem dubious outside of the home, the latter invention should be a mandatory garment for all politicians and bankers. Or, for the less adventurous, millinery fashionistas, how about a hat that reacts to ambient radio waves? We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions.

We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions. When it comes to music a generational gap has always been with us, separating young from old. Thus, without fail, parents will remark that the music listened to by their kids is loud and monotonous, nothing like the varied and much better music that they consumed in their younger days.

When it comes to music a generational gap has always been with us, separating young from old. Thus, without fail, parents will remark that the music listened to by their kids is loud and monotonous, nothing like the varied and much better music that they consumed in their younger days. Yet another research study of gender differences shows some fascinating variation in the way men and women see and process their perceptions of others. Men tend to be perceived as a whole, women, on the other hand, are more likely to be perceived as parts.

Yet another research study of gender differences shows some fascinating variation in the way men and women see and process their perceptions of others. Men tend to be perceived as a whole, women, on the other hand, are more likely to be perceived as parts.

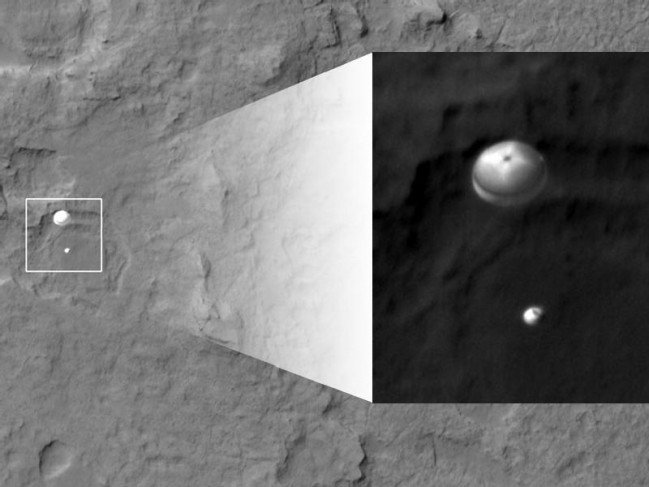

For the first time scientists have built a computer software model of an entire organism from its molecular building blocks. This allows the model to predict previously unobserved cellular biological processes and behaviors. While the organism in question is a simple bacterium, this represents another huge advance in computational biology.

For the first time scientists have built a computer software model of an entire organism from its molecular building blocks. This allows the model to predict previously unobserved cellular biological processes and behaviors. While the organism in question is a simple bacterium, this represents another huge advance in computational biology.

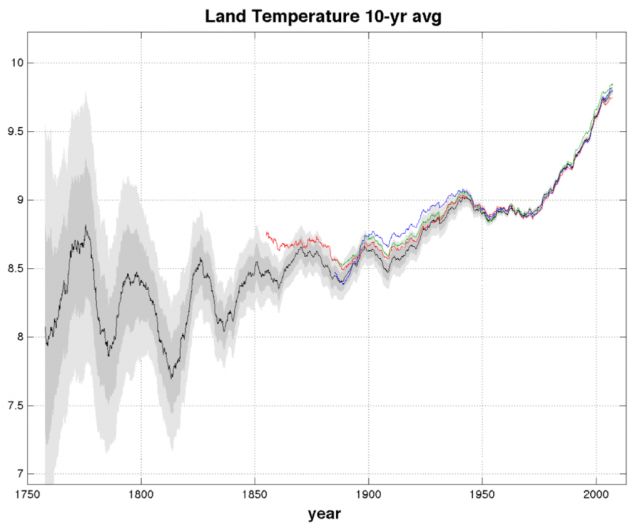

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben has been writing about climate change and environmental issues for over 20 years. His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989, and is considered to be the first book aimed at the general public on the subject of climate change.

Procrastinators have known this for a long time: that success comes from making a decision at the last possible moment.

Procrastinators have known this for a long time: that success comes from making a decision at the last possible moment.