Many of us see history — the school subject — as rather dull and boring. After all, how can the topic be made interesting when it’s usually taught by a coach who has other things on his or her mind [no joke, I have evidence of this from both sides of the Atlantic!].

Yet we also know that history’s lessons are essential to shaping our current world view and our vision for the future, in a myriad of ways. Since humans could speak and then write, our ancestors have recorded and transmitted their histories through oral storytelling, and then through books and assorted media.

Then came the internet. The explosion of content, media formats and related technologies over the last quarter-century has led to an immense challenge for archivists and historians intent on cataloging our digital stories. One facet of this challenge is the tremendous volume of information and its accelerating growth. Another is the dynamic nature of the content — much of it being constantly replaced and refreshed.

But, all is not lost. The Internet Archive founded in 1996 has been quietly archiving text, pages, images, audio and more recently entire web sites from the Tubes of the vast Internets. Currently the non-profit has archived around half a trillion web pages. It’s our modern day equivalent of the Library of Alexandria.

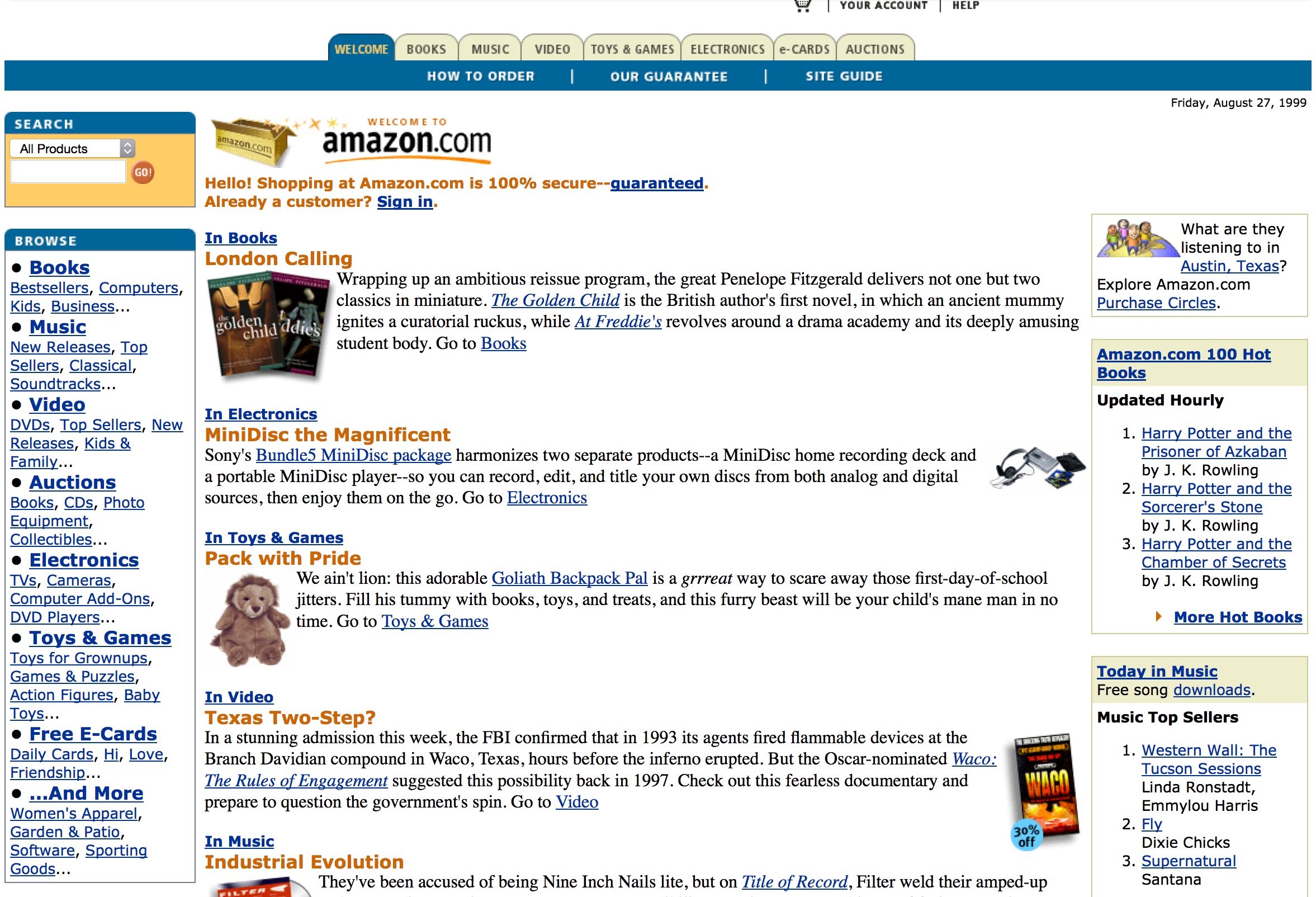

Please say hello to the Internet Archive Wayback Machine, and give it a try. The Wayback Machine took the screenshot above of Amazon.com in 1999, in case you’ve ever wondered what Amazon looked like before it swallowed or destroyed entire retail sectors.

From the New Yorker:

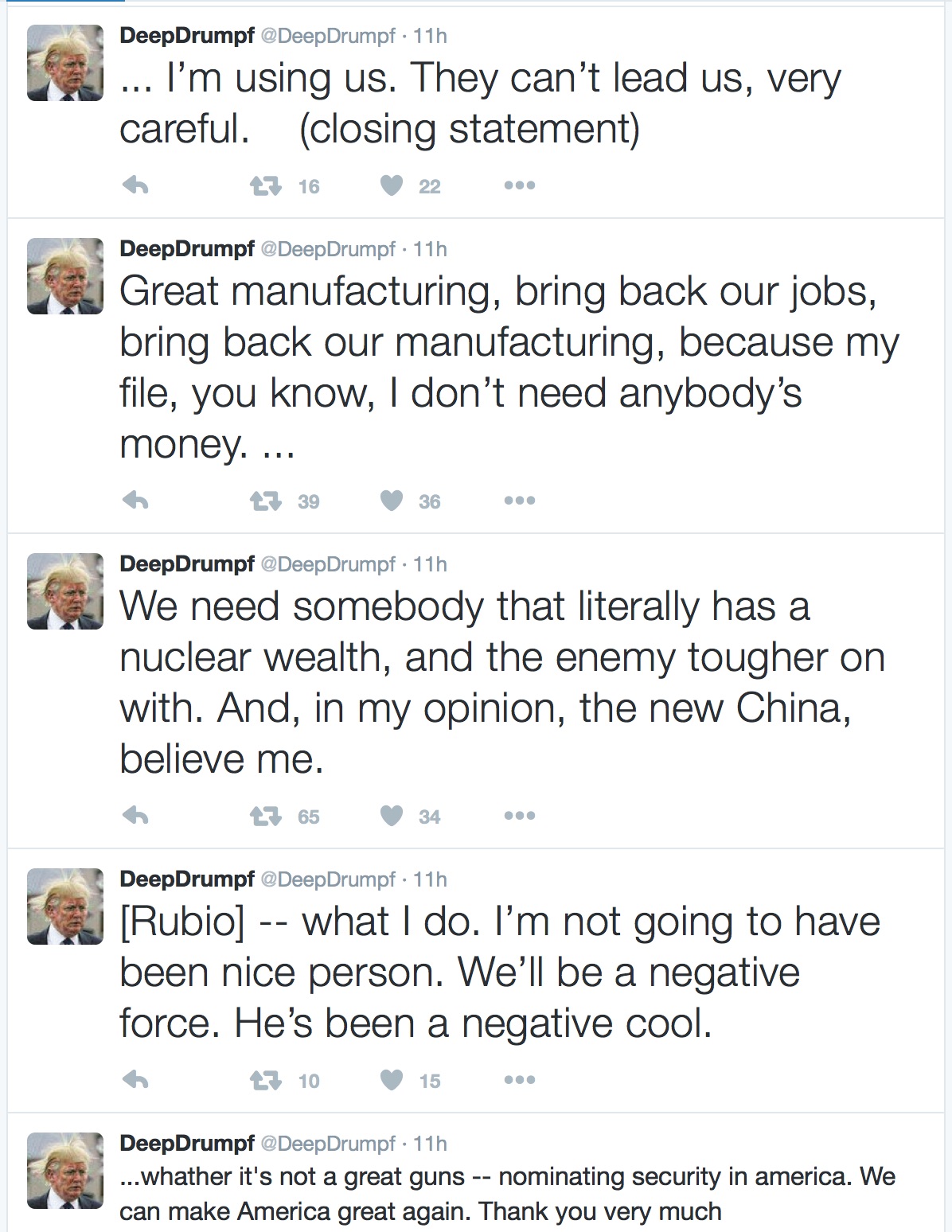

Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 took off from Amsterdam at 10:31 A.M. G.M.T. on July 17, 2014, for a twelve-hour flight to Kuala Lumpur. Not much more than three hours later, the plane, a Boeing 777, crashed in a field outside Donetsk, Ukraine. All two hundred and ninety-eight people on board were killed. The plane’s last radio contact was at 1:20 P.M. G.M.T. At 2:50 P.M. G.M.T., Igor Girkin, a Ukrainian separatist leader also known as Strelkov, or someone acting on his behalf, posted a message on VKontakte, a Russian social-media site: “We just downed a plane, an AN-26.” (An Antonov 26 is a Soviet-built military cargo plane.) The post includes links to video of the wreckage of a plane; it appears to be a Boeing 777.

Two weeks before the crash, Anatol Shmelev, the curator of the Russia and Eurasia collection at the Hoover Institution, at Stanford, had submitted to the Internet Archive, a nonprofit library in California, a list of Ukrainian and Russian Web sites and blogs that ought to be recorded as part of the archive’s Ukraine Conflict collection. Shmelev is one of about a thousand librarians and archivists around the world who identify possible acquisitions for the Internet Archive’s subject collections, which are stored in its Wayback Machine, in San Francisco. Strelkov’s VKontakte page was on Shmelev’s list. “Strelkov is the field commander in Slaviansk and one of the most important figures in the conflict,” Shmelev had written in an e-mail to the Internet Archive on July 1st, and his page “deserves to be recorded twice a day.”

On July 17th, at 3:22 P.M. G.M.T., the Wayback Machine saved a screenshot of Strelkov’s VKontakte post about downing a plane. Two hours and twenty-two minutes later, Arthur Bright, the Europe editor of the Christian Science Monitor, tweeted a picture of the screenshot, along with the message “Grab of Donetsk militant Strelkov’s claim of downing what appears to have been MH17.” By then, Strelkov’s VKontakte page had already been edited: the claim about shooting down a plane was deleted. The only real evidence of the original claim lies in the Wayback Machine.

The average life of a Web page is about a hundred days. Strelkov’s “We just downed a plane” post lasted barely two hours. It might seem, and it often feels, as though stuff on the Web lasts forever, for better and frequently for worse: the embarrassing photograph, the regretted blog (more usually regrettable not in the way the slaughter of civilians is regrettable but in the way that bad hair is regrettable). No one believes any longer, if anyone ever did, that “if it’s on the Web it must be true,” but a lot of people do believe that if it’s on the Web it will stay on the Web. Chances are, though, that it actually won’t. In 2006, David Cameron gave a speech in which he said that Google was democratizing the world, because “making more information available to more people” was providing “the power for anyone to hold to account those who in the past might have had a monopoly of power.” Seven years later, Britain’s Conservative Party scrubbed from its Web site ten years’ worth of Tory speeches, including that one. Last year, BuzzFeed deleted more than four thousand of its staff writers’ early posts, apparently because, as time passed, they looked stupider and stupider. Social media, public records, junk: in the end, everything goes.

Web pages don’t have to be deliberately deleted to disappear. Sites hosted by corporations tend to die with their hosts. When MySpace, GeoCities, and Friendster were reconfigured or sold, millions of accounts vanished. (Some of those companies may have notified users, but Jason Scott, who started an outfit called Archive Team—its motto is “We are going to rescue your shit”—says that such notification is usually purely notional: “They were sending e-mail to dead e-mail addresses, saying, ‘Hello, Arthur Dent, your house is going to be crushed.’ ”) Facebook has been around for only a decade; it won’t be around forever. Twitter is a rare case: it has arranged to archive all of its tweets at the Library of Congress. In 2010, after the announcement, Andy Borowitz tweeted, “Library of Congress to acquire entire Twitter archive—will rename itself Museum of Crap.” Not long after that, Borowitz abandoned that Twitter account. You might, one day, be able to find his old tweets at the Library of Congress, but not anytime soon: the Twitter Archive is not yet open for research. Meanwhile, on the Web, if you click on a link to Borowitz’s tweet about the Museum of Crap, you get this message: “Sorry, that page doesn’t exist!”

The Web dwells in a never-ending present. It is—elementally—ethereal, ephemeral, unstable, and unreliable. Sometimes when you try to visit a Web page what you see is an error message: “Page Not Found.” This is known as “link rot,” and it’s a drag, but it’s better than the alternative. More often, you see an updated Web page; most likely the original has been overwritten. (To overwrite, in computing, means to destroy old data by storing new data in their place; overwriting is an artifact of an era when computer storage was very expensive.) Or maybe the page has been moved and something else is where it used to be. This is known as “content drift,” and it’s more pernicious than an error message, because it’s impossible to tell that what you’re seeing isn’t what you went to look for: the overwriting, erasure, or moving of the original is invisible. For the law and for the courts, link rot and content drift, which are collectively known as “reference rot,” have been disastrous. In providing evidence, legal scholars, lawyers, and judges often cite Web pages in their footnotes; they expect that evidence to remain where they found it as their proof, the way that evidence on paper—in court records and books and law journals—remains where they found it, in libraries and courthouses. But a 2013 survey of law- and policy-related publications found that, at the end of six years, nearly fifty per cent of the URLs cited in those publications no longer worked. According to a 2014 study conducted at Harvard Law School, “more than 70% of the URLs within the Harvard Law Review and other journals, and 50% of the URLs within United States Supreme Court opinions, do not link to the originally cited information.” The overwriting, drifting, and rotting of the Web is no less catastrophic for engineers, scientists, and doctors. Last month, a team of digital library researchers based at Los Alamos National Laboratory reported the results of an exacting study of three and a half million scholarly articles published in science, technology, and medical journals between 1997 and 2012: one in five links provided in the notes suffers from reference rot. It’s like trying to stand on quicksand.

The footnote, a landmark in the history of civilization, took centuries to invent and to spread. It has taken mere years nearly to destroy. A footnote used to say, “Here is how I know this and where I found it.” A footnote that’s a link says, “Here is what I used to know and where I once found it, but chances are it’s not there anymore.” It doesn’t matter whether footnotes are your stock-in-trade. Everybody’s in a pinch. Citing a Web page as the source for something you know—using a URL as evidence—is ubiquitous. Many people find themselves doing it three or four times before breakfast and five times more before lunch. What happens when your evidence vanishes by dinnertime?

The day after Strelkov’s “We just downed a plane” post was deposited into the Wayback Machine, Samantha Power, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, told the U.N. Security Council, in New York, that Ukrainian separatist leaders had “boasted on social media about shooting down a plane, but later deleted these messages.” In San Francisco, the people who run the Wayback Machine posted on the Internet Archive’s Facebook page, “Here’s why we exist.”

Read the entire story here.

Image: Wayback Machine’s screenshot of Amazon.com’s home page, August 1999.

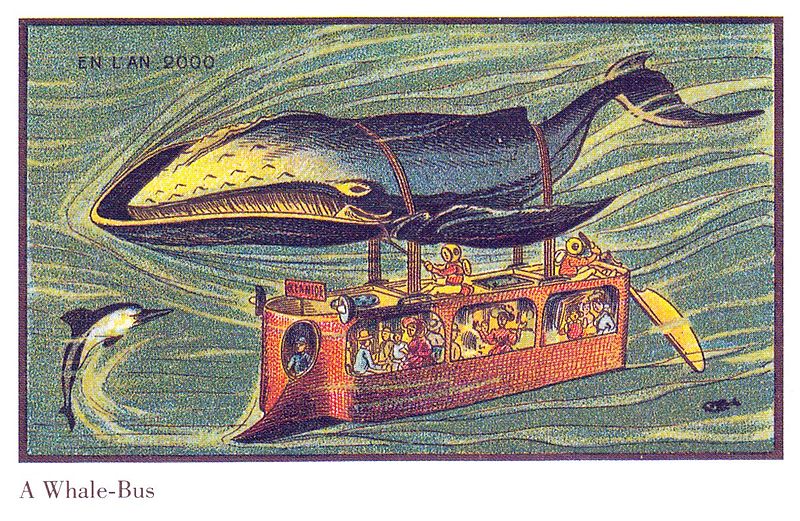

Businesses and brands come and they go. Seemingly unassailable corporations, often valued in the tens of billions of dollars (and sometimes more) fall to the incessant march of technological change and increasingly due to the ever fickle desires of the consumer.

Businesses and brands come and they go. Seemingly unassailable corporations, often valued in the tens of billions of dollars (and sometimes more) fall to the incessant march of technological change and increasingly due to the ever fickle desires of the consumer.

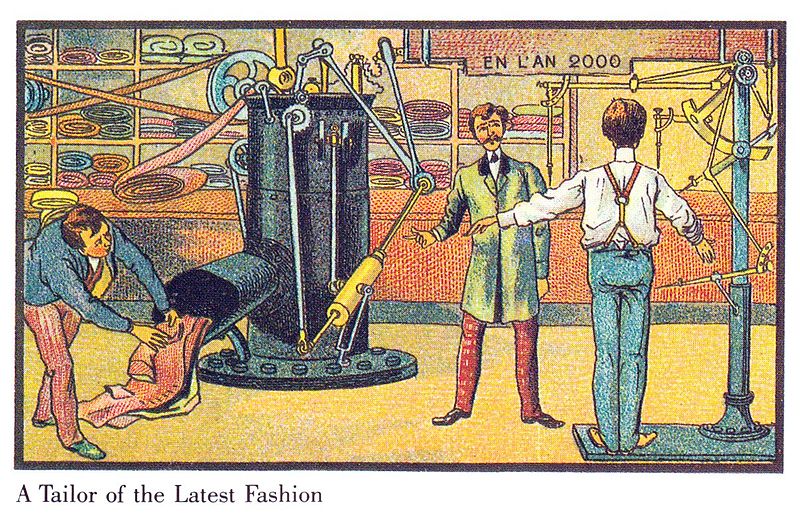

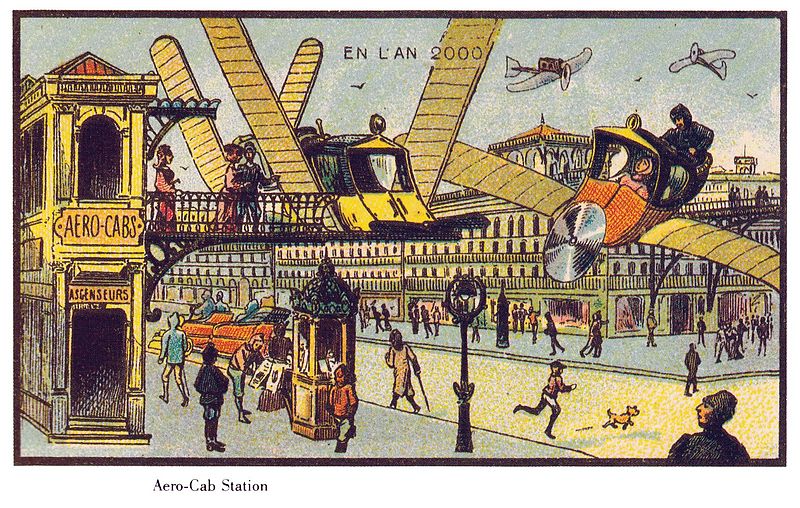

That said, even though it may still be a few years yet before we see traffic jams of driverless cars clogging the Interstate Highway system, some forward-thinkers are not resting on their laurels.

That said, even though it may still be a few years yet before we see traffic jams of driverless cars clogging the Interstate Highway system, some forward-thinkers are not resting on their laurels.