I’m not quite sure when the era of political correctness died, but surely our current election cycle truly signals its end. The pendulum of discourse has now swung fully away from PC to PS — Political Shamelessness.

I’m not quite sure when the era of political correctness died, but surely our current election cycle truly signals its end. The pendulum of discourse has now swung fully away from PC to PS — Political Shamelessness.

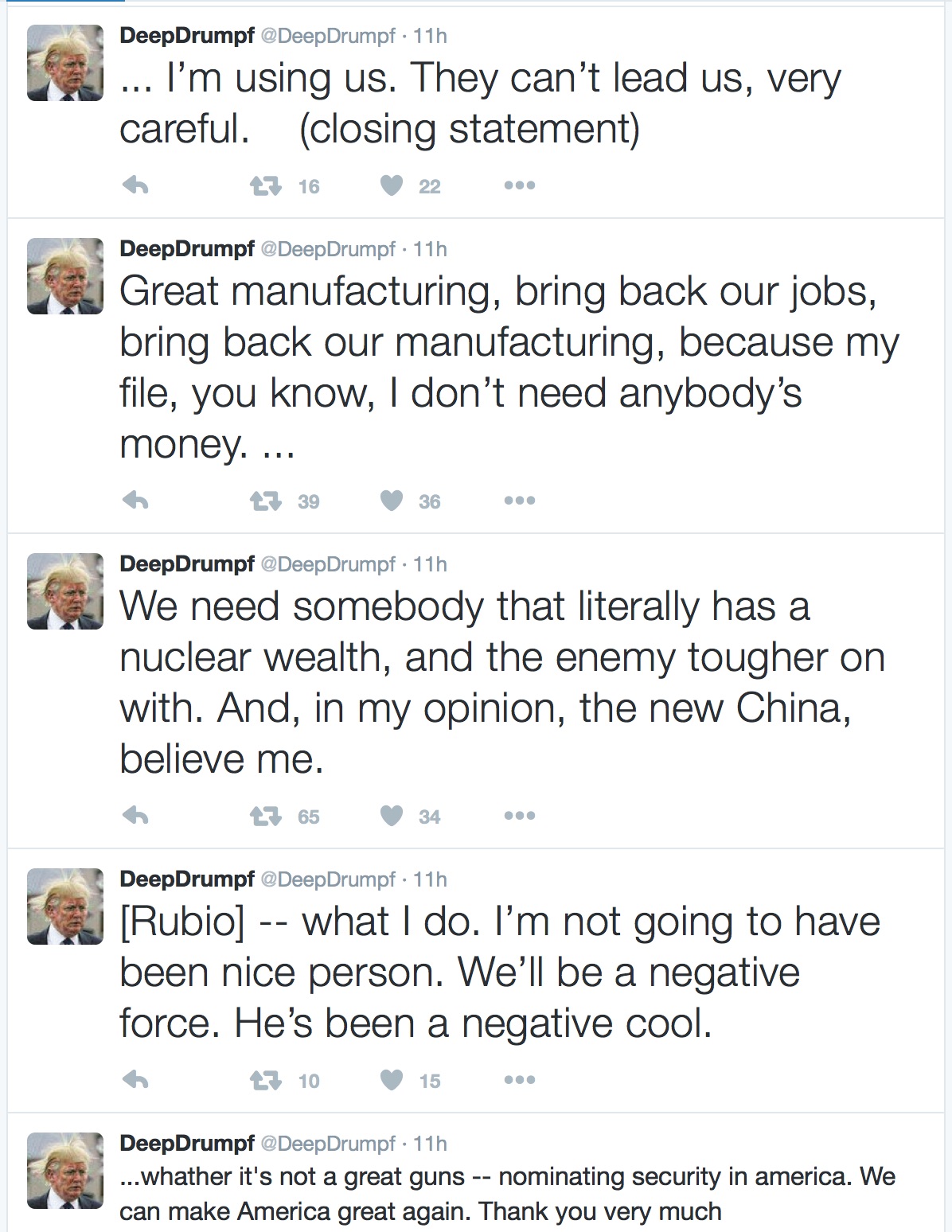

I suspect that the politically correct modus operandi of tip-toeing around substantive issues of our time is partly to blame for the rise of PS. Some commentators believe that PS is also fed by the shield of anonymity so perfectly enabled by our new online tools — anyone can now voice a vitriolic monologue behind a convenient anon avatar. Perhaps more so, our current culture has come to value blow-hard opinion disguised as news and hysterical reality TV re-packaged as real-life, and the more controversial, dramatic and bigoted the better.

Mark Leibovich, correspondent for NYT Magazine, looks at the roots and consequences of this epidemic of shameless public behavior. He’s quite right to assert that a “cesspool of anonymity” has facilitated a spike in indifference and shamelessness, and both are associated with false courage. Thus, it would seem that many of our public figures — especially our politicians — are petty cowards hiding behind a shield of untruth, bluster and anger. And, until we are all courageous enough to battle this tide of filthy discourse we will all continue to surf in the ocean of shamelessness.

From NYT Magazine:

Lately I’ve been thinking about the notion of false courage. It was introduced to me by an unlikely philosopher king: the Dallas Cowboys’ owner, Jerry Jones, whom I interviewed for an article on the N.F.L. that ran in the Feb. 7 issue of the magazine. We were talking about proposals on how to improve player safety in football. Jones mentioned to me a counterintuitive idea that Lamar Hunt, the founding owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, once suggested.

“Hunt thought we should take the face mask off of football helmets,” Jones told me. Why? Jones explained that face masks can foster an illusion of protection. “Lamar Hunt thought the face mask gave a player false courage,” Jones explained. “It gave the impression he could launch headfirst, and the face mask would protect him.”

I have since found myself thinking about false courage in other contexts. As a political culture, we are drowning in false courage. For all the exposure and exhibitionism that social media has allowed for, it has also has created a cesspool of anonymity — and what is anonymity if not a social face mask and sweeping enabler of false courage?

You can type pretty much anything you want these days with very little risk of discovery, let alone shame. People send me the most vile emails and tweets without any fear of anyone — namely me — learning who they are. I don’t much care; I am numb to their abuse. As with everyone who writes for the Internet, that is my default. I don’t mean to be glib here, especially as a man — I fully realize that for female writers, the line between run-of-the-mill Internet moron and a genuine threat can be hard to discern. But learned indifference is my face mask. No one gets embarrassed after a while because no one cares.

Last week, I wrote a brief article about Hillary Clinton. Nothing guarantees a faster descent into the cesspool than writing something — anything — about Hillary Clinton. I could list examples, but, you know, family newspaper. I received one particularly vulgar email via The Times’s feedback queue from a reader who identified himself as “Handsome Dave.” Without getting into his particular anatomical eloquences, I admit that I forwarded his note to a few friends with a sarcastic rejoinder about the quality of some of our readers. One person I sent Handsome Dave’s missive to was Tom Brokaw, the retired NBC News anchor, who has had a firsthand view of how fast our notions of common respect in the public discourse have disintegrated. Brokaw’s take on Handsome Dave: “It is that mentality and sense of empowerment that allows Trump to get away with his style.”

It’s always easy to roll eyes at traditional media types’ wringing hands over “the coarsening of our culture” or some such. But it’s also worth noting that the coarsening norms of the Internet can bear much resemblance these days to what’s actually coming from the candidates’ town halls and debate stages. Today’s politics nurtures its own ethic of false courage. For as scrutinized and unprivate as the lives of politicians have become, I would venture that they can get away with much more today than they used to; the speed of the news cycle, the shrinking of attention spans and the sheer volume of information practically dictates as much. People used to have time to digest information, and leaders were better regulated by higher capacities for shame. Community decency standards were higher. Everyone’s outrage reserves were much less overtaxed. Now everything burns off in a few days, no matter how noxious.

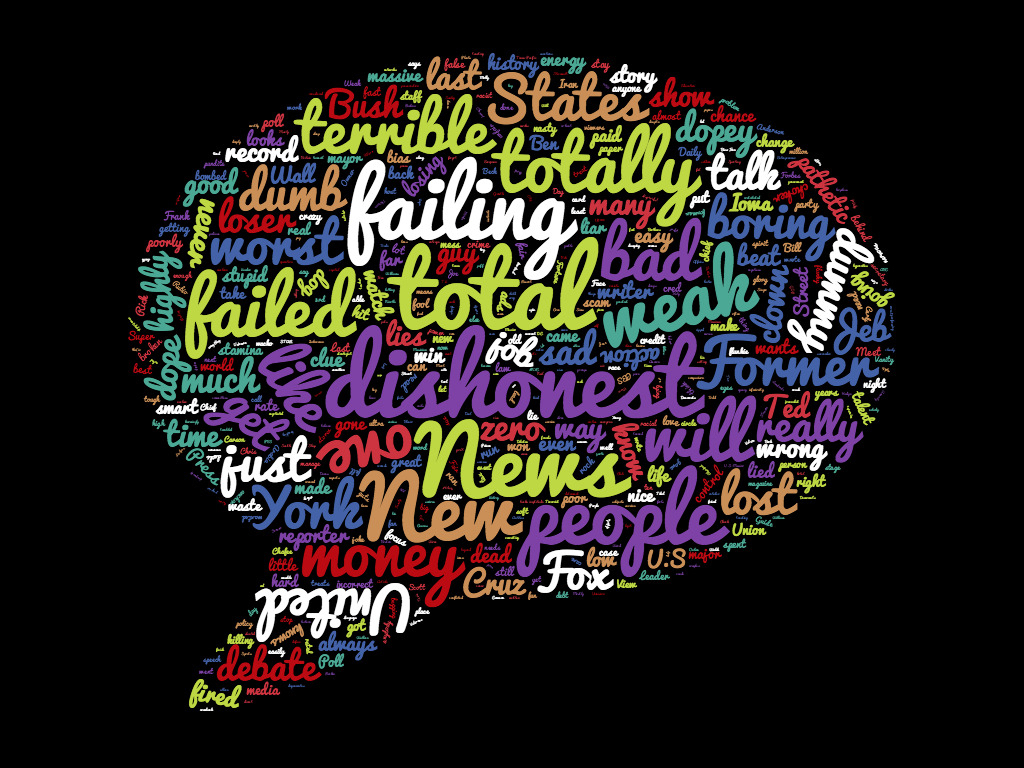

Brokaw mentioned Donald Trump. Trump is probably the best example of a politician that has insulated himself from the outrages he perpetrates by never apologizing, simply throwing himself into the next news cycle and explaining away what used to be called “gaffes” as proof of how honest and refreshing and nonpolitician-like his style is. But it’s not just Trump. All politicians today seem to operate with a greater sense of invulnerability — the belief that a deft media strategy can neutralize any consequences.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Dorothy meets the Cowardly Lion, from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz first edition. Courtesy: W.W. Denslow (d. 1915). Library of Congress. Public Domain.

The French have a formal language police.

The French have a formal language police.

A team of psychologists recently compiled and assessed the last words of prison inmates who were facing execution in Texas.

A team of psychologists recently compiled and assessed the last words of prison inmates who were facing execution in Texas.

Many political scholars, commentators and members of the public — of all political stripes — who remember

Many political scholars, commentators and members of the public — of all political stripes — who remember

Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?

Is Nicolas Felton the Samuel Pepys of our digital age?