A ingeniously simple and elegant idea brings sunshine to a small town in Norway.

From the Guardian:

On the market square in Rjukan stands a statue of the town’s founder, a noted Norwegian engineer and industrialist called Sam Eyde, sporting a particularly fine moustache. One hand thrust in trouser pocket, the other grasping a tightly rolled drawing, the great man stares northwards across the square at an almost sheer mountainside in front of him.

Behind him, to the south, rises the equally sheer 1,800-metre peak known as Gaustatoppen. Between the mountains, strung out along the narrow Vestfjord valley, lies the small but once mighty town that Eyde built in the early years of the last century, to house the workers for his factories.

He was plainly a smart guy, Eyde. He harnessed the power of the 100-metre Rjukanfossen waterfall to generate hydro-electricity in what was, at the time, the world’s biggest power plant. He pioneered new technologies – one of which bears his name – to produce saltpetre by oxidising nitrogen from air, and made industrial quantities of hydrogen by water electrolysis.

But there was one thing he couldn’t do: change the elevation of the sun. Deep in its east-west valley, surrounded by high mountains, Rjukan and its 3,400 inhabitants are in shadow for half the year. During the day, from late September to mid-March, the town, three hours’ north-west of Oslo, is not dark (well, it is almost, in December and January, but then so is most of Norway), but it’s certainly not bright either. A bit … flat. A bit subdued, a bit muted, a bit mono.

Since last week, however, Eyde’s statue has gazed out upon a sight that even the eminent engineer might have found startling. High on the mountain opposite, 450 metres above the town, three large, solar-powered, computer-controlled mirrors steadily track the movement of the sun across the sky, reflecting its rays down on to the square and bathing it in bright sunlight. Rjukan – or at least, a small but vital part of Rjukan – is no longer stuck where the sun don’t shine.

“It’s the sun!” grins Ingrid Sparbo, disbelievingly, lifting her face to the light and closing her eyes against the glare. A retired secretary, Sparbo has lived all her life in Rjukan and says people “do sort of get used to the shade. You end up not thinking about it, really. But this … This is so warming. Not just physically, but mentally. It’s mentally warming.”

Two young mothers wheel their children into the square, turn, and briefly bask: a quick hit. On a freezing day, an elderly couple sit wide-eyed on one of the half-dozen newly installed benches, smiling at the warmth on their faces. Children beam. Lots of people take photographs. A shop assistant, Silje Johansen, says it’s “awesome. Just awesome.”

Pushing his child’s buggy, electrical engineer Eivind Toreid is more cautious. “It’s a funny thing,” he says. “Not real sunlight, but very like it. Like a spotlight. I’ll go if I’m free and in town, yes. Especially in autumn and in the weeks before the sun comes back. Those are the worst: you look just a short way up the mountainside and the sun is right there, so close you can almost touch it. But not here.”

Pensioners Valborg and Eigil Lima have driven from Stavanger – five long hours on the road – specially to see it. Heidi Fieldheim, who lives in Oslo now but spent six years in Rjukan with her husband, a local man, says she heard all about it on the radio. “But it’s far more than I expected,” she says. “This will bring much happiness.”

Across the road in the Nyetider cafe, sporting – by happy coincidence – a particularly fine set of mutton chops, sits the man responsible for this unexpected access to happiness. Martin Andersen is a 40-year-old artist and lifeguard at the municipal baths who, after spells in Berlin, Paris, Mali and Oslo, pitched up in Rjukan in the summer of 2001.

The first inkling of an artwork Andersen dubbed the Solspeil, or sun mirror, came to him as the month of September began to fade: “Every day, we would take our young child for a walk in the buggy,” he says, “and every day I realised we were having to go a little further down the valley to find the sun.” By 28 September, Andersen realised, the sun completely disappears from Rjukan’s market square. The occasion of its annual reappearance, lighting up the bridge across the river by the old fire station, is a date indelibly engraved in the minds of all Rjukan residents: 12 March.

And throughout the seemingly endless intervening months, Andersen says: “We’d look up and see blue sky above, and the sun high on the mountain slopes, but the only way we could get to it was to go out of town. The brighter the day, the darker it was down here. And it’s sad, a town that people have to leave in order to feel the sun.”

A hundred years ago, Eyde had already grasped the gravity of the problem. Researching his own plan, Andersen discovered that, as early as 1913, Eyde was considering a suggestion by one of his factory workers for a system of mountain-top mirrors to redirect sunlight into the valley below.

The industrialist eventually abandoned the plan for want of adequate technology, but soon afterwards his company, Norsk Hydro, paid for the construction of a cable car to carry the long-suffering townsfolk, for a modest sum, nearly 500m higher up the mountain and into the sunlight. (Built in 1928, the Krossobanen is still running, incidentally; £10 for the return trip. The view is majestic and the coffee at the top excellent. A brass plaque in the ticket office declares the facility a gift from the company “to the people of Rjukan, because for six months of the year, the sun does not shine in the bottom of the valley”.)

Andersen unearthed a partially covered sports stadium in Arizona that was successfully using small mirrors to keep its grass growing. He learned that in the Middle East and other sun-baked regions of the world, vast banks of hi-tech tracking mirrors called heliostats concentrate sufficient reflected sunlight to heat steam turbines and drive whole power plants.He persuaded the town hall to come up with the cash to allow him to develop his project further. He contacted an expert in the field, Jonny Nersveen, who did the maths and told him it could probably work. He visited Viganella, an Italian village that installed a similar sun mirror in 2006.

And 12 years after he first dreamed of his Solspeil, a German company specialising in so-called CSP – concentrated solar power – helicoptered in the three 17 sq m glass mirrors that now stand high above the market square in Rjukan. “It took,” he says, “a bit longer than we’d imagined.” First, the municipality wasn’t used to dealing with this kind of project: “There’s no rubber stamp for a sun mirror.” But Andersen also wanted to be sure it was right – that Rjukan’s sun mirror would do what it was intended to do.

Viganella’s single polished steel mirror, he says, lights a much larger area, but with a far weaker, more diffuse light. “I wanted a smaller, concentrated patch of sunlight: a special sunlit spot in the middle of town where people could come for a quick five minutes in the sun.” The result, you would have to say, is pretty much exactly that: bordered on one side by the library and town hall, and on the other by the tourist office, the 600 sq ms of Rjukan’s market square, to be comprehensively remodelled next year in celebration, now bathes in a focused beam of bright sunlight fully 80-90% as intense as the original.

Their efforts monitored by webcams up on the mountain and down in the square, their movement dictated by computer in a Bavarian town outside Munich, the heliostats generate the solar power they need to gradually tilt and rotate, following the sun on its brief winter dash across the sky.

It really works. Even the objectors – and there were, in town, plenty of them; petitions and letter-writing campaigns and a Facebook page organised against what a large number of locals saw initially as a vanity project and, above all, a criminal waste of money – now seem largely won over.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Light reflected by the mirrors of Rjukan, Norway. Courtesy of David Levene / Guardian.

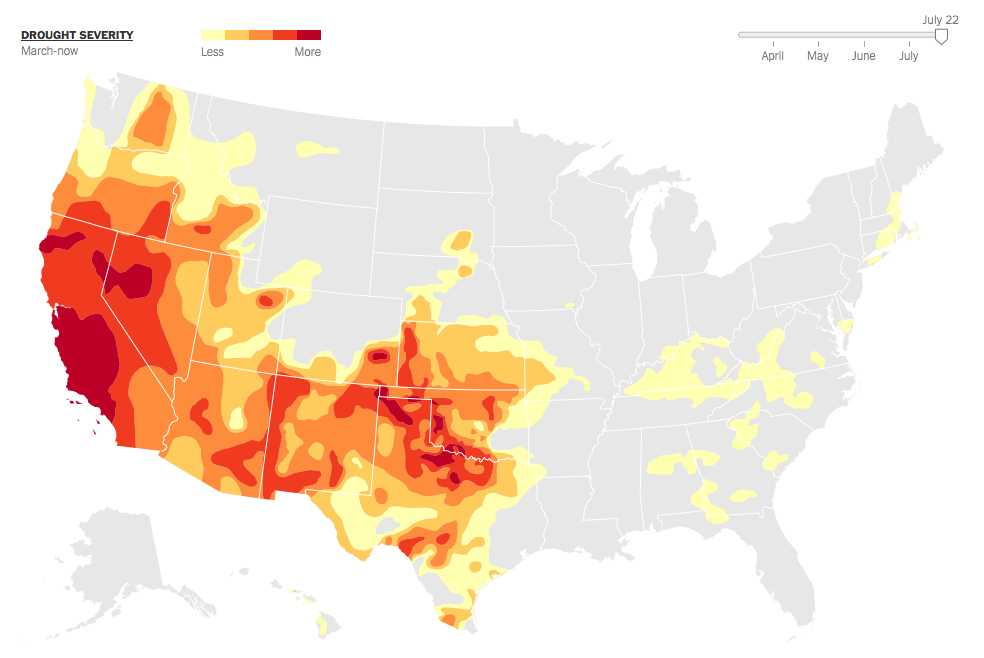

The NYT has an fascinating and detailed article bursting with charts and statistics that shows the pervasive grip of the drought in the United States. The desert Southwest and West continue to be parched and scorching. This is not a pretty picture for farmers and increasingly for those (sub-)urban dwellers who rely upon a fragile and dwindling water supply.

The NYT has an fascinating and detailed article bursting with charts and statistics that shows the pervasive grip of the drought in the United States. The desert Southwest and West continue to be parched and scorching. This is not a pretty picture for farmers and increasingly for those (sub-)urban dwellers who rely upon a fragile and dwindling water supply.