It’s interesting to ponder what would have been if the internet and social media had been around during those more fractious times in Seneca Falls, Selma and Stonewall. Perhaps these tools would have helped accelerate progress.

[div class-attrib]From Technology Review:[end-div]

A decade-plus of anthropological fieldwork among hackers and like-minded geeks has led me to the firm conviction that these people are building one of the most vibrant civil liberties movements we’ve ever seen. It is a culture committed to freeing information, insisting on privacy, and fighting censorship, which in turn propels wide-ranging political activity. In the last year alone, hackers have been behind some of the most powerful political currents out there.

Before I elaborate, a brief word on the term “hacker” is probably in order. Even among hackers, it provokes debate. For instance, on the technical front, a hacker might program, administer a network, or tinker with hardware. Ethically and politically, the variability is just as prominent. Some hackers are part of a transgressive, law-breaking tradition, their activities opaque and below the radar. Other hackers write open-source software and pride themselves on access and transparency. While many steer clear of political activity, an increasingly important subset rise up to defend their productive autonomy, or engage in broader social justice and human rights campaigns.

Despite their differences, there are certain websites and conferences that bring the various hacker clans together. Like any political movement, it is internally diverse but, under the right conditions, individuals with distinct abilities will work in unison toward a cause.

Take, for instance, the reaction to the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a far-reaching copyright bill meant to curtail piracy online. SOPA was unraveled before being codified into law due to a massive and elaborate outpouring of dissent driven by the hacker movement.

The linchpin was a “Blackout Day”—a Web-based protest of unprecedented scale. To voice their opposition to the bill, on January 17, 2012, nonprofits, some big Web companies, public interest groups, and thousands of individuals momentarily removed their websites from the Internet and thousands of other citizens called or e-mailed their representatives. Journalists eventually wrote a torrent of articles. Less than a week later, in response to these stunning events, SOPA and PIPA, its counterpart in the Senate, were tabled (see “SOPA Battle Won, but War Continues”).

The victory hinged on its broad base of support cultivated by hackers and geeks. The participation of corporate giants like Google, respected Internet personalities like Jimmy Wales, and the civil liberties organization EFF was crucial to its success. But the geek and hacker contingent was palpably present, and included, of course, Anonymous. Since 2008, activists have rallied under this banner to initiate targeted demonstrations, publicize various wrongdoings, leak sensitive data, engage in digital direct action, and provide technology assistance for revolutionary movements.

As part of the SOPA protests, Anonymous churned out videos and propaganda posters and provided constant updates on several prominent Twitter accounts, such as Your Anonymous News, which are brimming with followers. When the blackout ended, corporate players naturally receded from the limelight and went back to work. Anonymous and others, however, continue to fight for Internet freedoms.

In fact, just the next day, on January 18, 2012, federal authorities orchestrated the takedown of the popular file-sharing site MegaUpload. The company’s gregarious and controversial founder Kim Dotcom was also arrested in a dramatic early morning raid in New Zealand. The removal of this popular website was received ominously by Anonymous activists: it seemed to confirm that if bills like SOPA become law, censorship would become a far more common fixture on the Internet. Even though no court had yet found Kim Dotcom guilty of piracy, his property was still confiscated and his website knocked off the Internet.

As soon as the news broke, Anonymous coordinated its largest distributed denial of service campaign to date. It took down a slew of websites, including the homepage of Universal Music, the FBI, the U.S. Copyright Office, the Recording Industry Association of America, and the Motion Picture Association of America.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

The gods of Norse legend are surely turning slowly in their graves. A Reykjavik, Iceland, court recently granted a 15-year-old the right to use her given name. Her first name, “Blaer” means “light breeze” in Icelandic, and until the ruling was not permitted to use the name under Iceland’s strict cultural preservation laws. So, before you name your next child Shoniqua or Te’o or Cruise, pause for a few moments to think how lucky you are that you live elsewhere (with apologies to our readers in Iceland).

The gods of Norse legend are surely turning slowly in their graves. A Reykjavik, Iceland, court recently granted a 15-year-old the right to use her given name. Her first name, “Blaer” means “light breeze” in Icelandic, and until the ruling was not permitted to use the name under Iceland’s strict cultural preservation laws. So, before you name your next child Shoniqua or Te’o or Cruise, pause for a few moments to think how lucky you are that you live elsewhere (with apologies to our readers in Iceland).

The United Kingdom government has just published its updated 180-page handbook for new residents. So, those seeking to become subjects of Her Majesty will need to brush up on more that Admiral Nelson, Churchill, Spitfires, Chaucer and the Black Death. Now, if you are one of the approximately 150,000 new residents each year, you may well have to learn about Morecambe and Wise, Roald Dahl, and Monty Python. Nudge-nudge, wink-wink!

The United Kingdom government has just published its updated 180-page handbook for new residents. So, those seeking to become subjects of Her Majesty will need to brush up on more that Admiral Nelson, Churchill, Spitfires, Chaucer and the Black Death. Now, if you are one of the approximately 150,000 new residents each year, you may well have to learn about Morecambe and Wise, Roald Dahl, and Monty Python. Nudge-nudge, wink-wink!

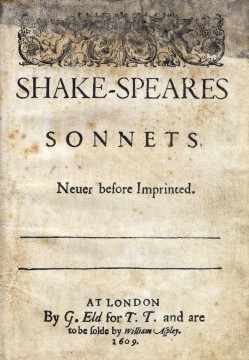

One great writer reflects on the influences of another.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another. The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

Leaving the merits of capitalism or socialism aside for a moment, let’s consider the case for taxing bad behavior versus good. Adam Davidson, economics columnist and founder of NPR’s Planet Money, reviews the case now being made by a growing number of economists on both the left and the right. They all come to a similar conclusion: Forget about taxing good or constrictive behavior such as entrepreneurialism. Rather, it’s time to tax people for doing destructive and damaging things.

Leaving the merits of capitalism or socialism aside for a moment, let’s consider the case for taxing bad behavior versus good. Adam Davidson, economics columnist and founder of NPR’s Planet Money, reviews the case now being made by a growing number of economists on both the left and the right. They all come to a similar conclusion: Forget about taxing good or constrictive behavior such as entrepreneurialism. Rather, it’s time to tax people for doing destructive and damaging things.

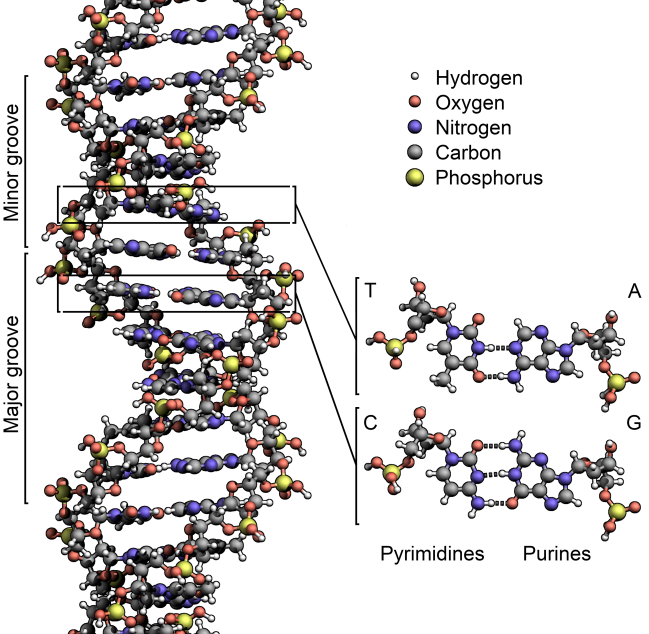

Cosmologists theorized the need for dark matter to account for hidden mass in our universe. Yet, as the name implies, it is proving rather hard to find. Now astronomers believe they see hints of it in ancient galactic collisions.

Cosmologists theorized the need for dark matter to account for hidden mass in our universe. Yet, as the name implies, it is proving rather hard to find. Now astronomers believe they see hints of it in ancient galactic collisions. Having missed the recent apocalypse said to have been predicted by the Mayans, the next possible end of the world is set for 2036. This time it’s courtesy of aptly named asteroid – Apophis.

Having missed the recent apocalypse said to have been predicted by the Mayans, the next possible end of the world is set for 2036. This time it’s courtesy of aptly named asteroid – Apophis.