Technologist Marc Goodman describes a not too distant future in which all our appliances, tools, products… anything and everything is plugged into the so-called Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT describes a world where all things are connected to everything else, making for a global mesh of intelligent devices from your connected car and your WiFi enabled sneakers to your smartwatch and home thermostat. You may well believe it advantageous to have your refrigerator ping the local grocery store when it runs out of fresh eggs and milk or to have your toilet auto-call a local plumber when it gets stopped-up.

But, as our current Internet shows us — let’s call it the Internet of People — not all is rosy in this hyper-connected, 24/7, always-on digital ocean. What are you to do when hackers attack all your home appliances in a “denial of home service attack (DohS)”, or when your every move inside your home is scrutinized, collected, analyzed and sold to the nearest advertiser, or when your cooktop starts taking and sharing selfies with the neighbors?

Goodman’s new book on this important subject, excerpted here, is titled Future Crimes.

From the Guardian:

If we think of today’s internet metaphorically as about the size of a golf ball, tomorrow’s will be the size of the sun. Within the coming years, not only will every computer, phone and tablet be online, but so too will every car, house, dog, bridge, tunnel, cup, clock, watch, pacemaker, cow, streetlight, bridge, tunnel, pipeline, toy and soda can. Though in 2013 there were only 13bn online devices, Cisco Systems has estimated that by 2020 there will be 50bn things connected to the internet, with room for exponential growth thereafter. As all of these devices come online and begin sharing data, they will bring with them massive improvements in logistics, employee efficiency, energy consumption, customer service and personal productivity.

This is the promise of the internet of things (IoT), a rapidly emerging new paradigm of computing that, when it takes off, may very well change the world we live in forever.

The Pew Research Center defines the internet of things as “a global, immersive, invisible, ambient networked computing environment built through the continued proliferation of smart sensors, cameras, software, databases, and massive data centres in a world-spanning information fabric”. Back in 1999, when the term was first coined by MIT researcher Kevin Ashton, the technology did not exist to make the IoT a reality outside very controlled environments, such as factory warehouses. Today we have low-powered, ultra-cheap computer chips, some as small as the head of a pin, that can be embedded in an infinite number of devices, some for mere pennies. These miniature computing devices only need milliwatts of electricity and can run for years on a minuscule battery or small solar cell. As a result, it is now possible to make a web server that fits on a fingertip for $1.

The microchips will receive data from a near-infinite range of sensors, minute devices capable of monitoring anything that can possibly be measured and recorded, including temperature, power, location, hydro-flow, radiation, atmospheric pressure, acceleration, altitude, sound and video. They will activate miniature switches, valves, servos, turbines and engines – and speak to the world using high-speed wireless data networks. They will communicate not only with the broader internet but with each other, generating unfathomable amounts of data. The result will be an always-on “global, immersive, invisible, ambient networked computing environment”, a mere prelude to the tidal wave of change coming next.

…

In the future all objects may be smart

The broad thrust sounds rosy. Because chips and sensors will be embedded in everyday objects, we will have much better information and convenience in our lives. Because your alarm clock is connected to the internet, it will be able to access and read your calendar. It will know where and when your first appointment of the day is and be able to cross-reference that information against the latest traffic conditions. Light traffic, you get to sleep an extra 10 minutes; heavy traffic, and you might find yourself waking up earlier than you had hoped.

When your alarm does go off, it will gently raise the lights in the house, perhaps turn up the heat or run your bath. The electronic pet door will open to let Fido into the backyard for his morning visit, and the coffeemaker will begin brewing your coffee. You won’t have to ask your kids if they’ve brushed their teeth; the chip in their toothbrush will send a message to your smartphone letting you know the task is done. As you walk out the door, you won’t have to worry about finding your keys; the beacon sensor on the key chain makes them locatable to within two inches. It will be as if the Jetsons era has finally arrived.

While the hype-o-meter on the IoT has been blinking red for some time, everything described above is already technically feasible. To be certain, there will be obstacles, in particular in relation to a lack of common technical standards, but a wide variety of companies, consortia and government agencies are hard at work to make the IoT a reality. The result will be our transition from connectivity to hyper-connectivity, and like all things Moore’s law related, it will be here sooner than we realise.

The IoT means that all physical objects in the future will be assigned an IP address and be transformed into information technologies. As a result, your lamp, cat or pot plant will be part of an IT network. Things that were previously silent will now have a voice, and every object will be able to tell its own story and history. The refrigerator will know exactly when it was manufactured, the names of the people who built it, what factory it came from, and the day it left the assembly line, arrived at the retailer, and joined your home network. It will keep track of every time its door has been opened and which one of your kids forgot to close it. When the refrigerator’s motor begins to fail, it can signal for help, and when it finally dies, it will tell us how to disassemble its parts and best recycle them. Buildings will know every person who has ever worked there, and streetlights every car that has ever driven by.

All of these objects will communicate with each other and have access to the massive processing and storage power of the cloud, further enhanced by additional mobile and social networks. In the future all objects may become smart, in fact much smarter than they are today, and as these devices become networked, they will develop their own limited form of sentience, resulting in a world in which people, data and things come together. As a consequence of the power of embedded computing, we will see billions of smart, connected things joining a global neural network in the cloud.

In this world, the unknowable suddenly becomes knowable. For example, groceries will be tracked from field to table, and restaurants will keep tabs on every plate, what’s on it, who ate from it, and how quickly the waiters are moving it from kitchen to customer. As a result, when the next E coli outbreak occurs, we won’t have to close 500 eateries and wonder if it was the chicken or beef that caused the problem. We will know exactly which restaurant, supplier and diner to contact to quickly resolve the problem. The IoT and its billions of sensors will create an ambient intelligence network that thinks, senses and feels and contributes profoundly to the knowable universe.

Things that used to make sense suddenly won’t, such as smoke detectors. Why do most smoke detectors do nothing more than make loud beeps if your life is in mortal danger because of fire? In the future, they will flash your bedroom lights to wake you, turn on your home stereo, play an MP3 audio file that loudly warns, “Fire, fire, fire.” They will also contact the fire department, call your neighbours (in case you are unconscious and in need of help), and automatically shut off flow to the gas appliances in the house.

The byproduct of the IoT will be a living, breathing, global information grid, and technology will come alive in ways we’ve never seen before, except in science fiction movies. As we venture down the path toward ubiquitous computing, the results and implications of the phenomenon are likely to be mind-blowing. Just as the introduction of electricity was astonishing in its day, it eventually faded into the background, becoming an imperceptible, omnipresent medium in constant interaction with the physical world. Before we let this happen, and for all the promise of the IoT, we must ask critically important questions about this brave new world. For just as electricity can shock and kill, so too can billions of connected things networked online.

One of the central premises of the IoT is that everyday objects will have the capacity to speak to us and to each other. This relies on a series of competing communications technologies and protocols, many of which are eminently hackable. Take radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology, considered by many the gateway to the IoT. Even if you are unfamiliar with the name, chances are you have already encountered it in your life, whether it’s the security ID card you use to swipe your way into your office, your “wave and pay” credit card, the key to your hotel room, your Oyster card.

…

Even if you don’t use an RFID card for work, there’s a good chance you either have it or will soon have it embedded in the credit card sitting in your wallet. Hackers have been able to break into these as well, using cheap RFID readers available on eBay for just $50, tools that allow an attacker to wirelessly capture a target’s credit card number, expiration date and security code. Welcome to pocket picking 2.0.

More productive and more prison-like

A much rarer breed of hacker targets the physical elements that make up a computer system, including the microchips, electronics, controllers, memory, circuits, components, transistors and sensors – core elements of the internet of things. These hackers attack a device’s firmware, the set of computer instructions present on every electronic device we encounter, including TVs, mobile phones, game consoles, digital cameras, network routers, alarm systems, CCTVs, USB drives, traffic lights, gas station pumps and smart home management systems. Before we add billions of hackable things and communicate with hackable data transmission protocols, important questions must be asked about the risks for the future of security, crime, terrorism, warfare and privacy.

In the same way our every move online can be tracked, recorded, sold and monetised today, so too will that be possible in the near future in the physical world. Real space will become just like cyberspace. With the widespread adoption of more networked devices, what people do in their homes, cars, workplaces, schools and communities will be subjected to increased monitoring and analysis by the corporations making these devices. Of course these data will be resold to advertisers, data brokers and governments, providing an unprecedented view into our daily lives. Unfortunately, just like our social, mobile, locational and financial information, our IoT data will leak, providing further profound capabilities to stalkers and other miscreants interested in persistently tracking us. While it would certainly be possible to establish regulations and build privacy protocols to protect consumers from such activities, the greater likelihood is that every IoT-enabled device, whether an iron, vacuum, refrigerator, thermostat or lightbulb, will come with terms of service that grant manufacturers access to all your data. More troublingly, while it may be theoretically possible to log off in cyberspace, in your well-connected smart home there will be no “opt-out” provision.

We may find ourselves interacting with thousands of little objects around us on a daily basis, each collecting seemingly innocuous bits of data 24/7, information these things will report to the cloud, where it will be processed, correlated, and reviewed. Your smart watch will reveal your lack of exercise to your health insurance company, your car will tell your insurer of your frequent speeding, and your dustbin will tell your local council that you are not following local recycling regulations. This is the “internet of stool pigeons”, and though it may sound far-fetched, it’s already happening. Progressive, one of the largest US auto insurance companies, offers discounted personalised rates based on your driving habits. “The better you drive, the more you can save,” according to its advertising. All drivers need to do to receive the lower pricing is agree to the installation of Progressive’s Snapshot black-box technology in their cars and to having their braking, acceleration and mileage persistently tracked.

The IoT will also provide vast new options for advertisers to reach out and touch you on every one of your new smart connected devices. Every time you go to your refrigerator to get ice, you will be presented with ads for products based on the food your refrigerator knows you’re most likely to buy. Screens too will be ubiquitous, and marketers are already planning for the bounty of advertising opportunities. In late 2013, Google sent a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission noting, “we and other companies could [soon] be serving ads and other content on refrigerators, car dashboards, thermostats, glasses and watches, to name just a few possibilities.”

Knowing that Google can already read your Gmail, record your every web search, and track your physical location on your Android mobile phone, what new powerful insights into your personal life will the company develop when its entertainment system is in your car, its thermostat regulates the temperature in your home, and its smart watch monitors your physical activity?

Not only will RFID and other IoT communications technologies track inanimate objects, they will be used for tracking living things as well. The British government has considered implanting RFID chips directly under the skin of prisoners, as is common practice with dogs. School officials across the US have begun embedding RFID chips in student identity cards, which pupils are required to wear at all times. In Contra Costa County, California, preschoolers are now required to wear basketball-style jerseys with electronic tracking devices built in that allow teachers and administrators to know exactly where each student is. According to school district officials, the RFID system saves “3,000 labour hours a year in tracking and processing students”.

Meanwhile, the ability to track employees, how much time they take for lunch, the length of their toilet breaks and the number of widgets they produce will become easy. Moreover, even things such as words typed per minute, eye movements, total calls answered, respiration, time away from desk and attention to detail will be recorded. The result will be a modern workplace that is simultaneously more productive and more prison-like.

At the scene of a suspected crime, police will be able to interrogate the refrigerator and ask the equivalent of, “Hey, buddy, did you see anything?” Child social workers will know there haven’t been any milk or nappies in the home, and the only thing stored in the fridge has been beer for the past week. The IoT also opens up the world for “perfect enforcement”. When sensors are everywhere and all data is tracked and recorded, it becomes more likely that you will receive a moving violation for going 26 miles per hour in a 25-mile-per-hour zone and get a parking ticket for being 17 seconds over on your meter.

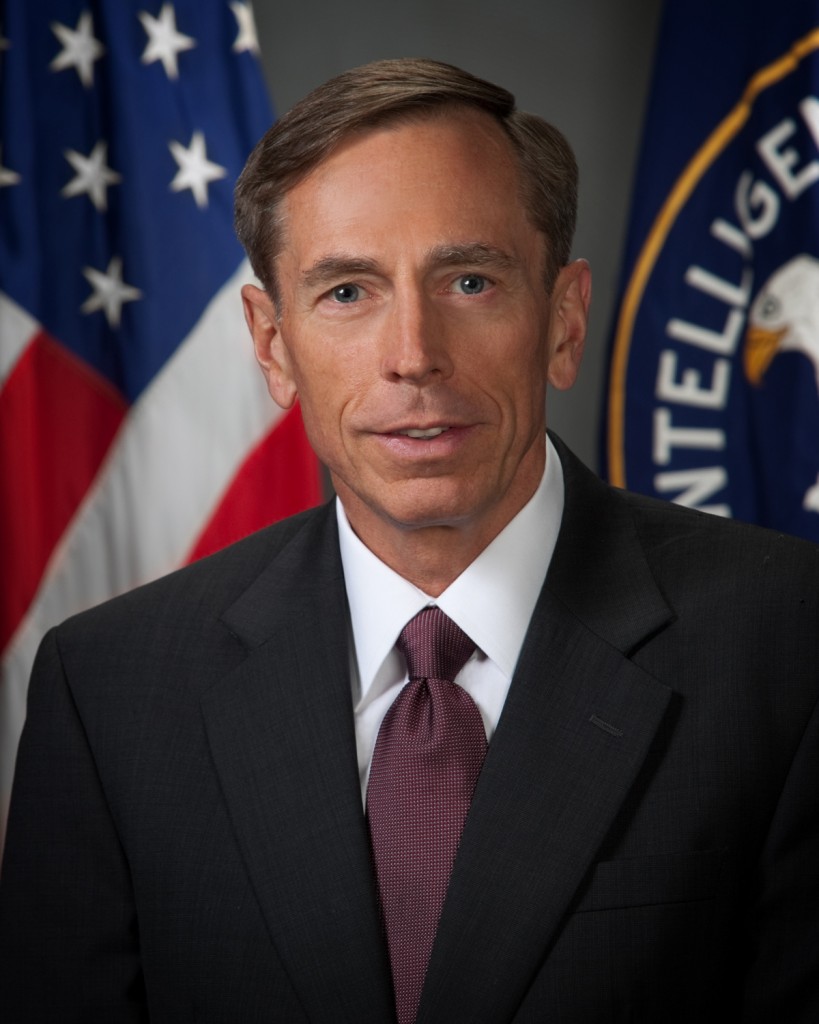

The former CIA director David Petraeus has noted that the IoT will be “transformational for clandestine tradecraft”. While the old model of corporate and government espionage might have involved hiding a bug under the table, tomorrow the very same information might be obtained by intercepting in real time the data sent from your Wi-Fi lightbulb to the lighting app on your smart phone. Thus the devices you thought were working for you may in fact be on somebody else’s payroll, particularly that of Crime, Inc.

A network of unintended consequences

For all the untold benefits of the IoT, its potential downsides are colossal. Adding 50bn new objects to the global information grid by 2020 means that each of these devices, for good or ill, will be able to potentially interact with the other 50bn connected objects on earth. The result will be 2.5 sextillion potential networked object-to-object interactions – a network so vast and complex it can scarcely be understood or modelled. The IoT will be a global network of unintended consequences and black swan events, ones that will do things nobody ever planned. In this world, it is impossible to know the consequences of connecting your home’s networked blender to the same information grid as an ambulance in Tokyo, a bridge in Sydney, or a Detroit auto manufacturer’s production line.

The vast levels of cyber crime we currently face make it abundantly clear we cannot even adequately protect the standard desktops and laptops we presently have online, let alone the hundreds of millions of mobile phones and tablets we are adding annually. In what vision of the future, then, is it conceivable that we will be able to protect the next 50bn things, from pets to pacemakers to self-driving cars? The obvious reality is that we cannot.

Our technological threat surface area is growing exponentially and we have no idea how to defend it effectively. The internet of things will become nothing more than the Internet of things to be hacked.

Read the entire article here.

Image courtesy of Google Search.

Government officials in Florida are barred from using the terms “climate change”, “global warming”, “sustainable” and other related terms. Apparently, they’ll have to use the euphemism “nuisance flooding” in place of “sea-level rise”. One wonders what literary trick they’ll conjure up next time the state gets hit by a hurricane — “Oh, that? Just a ‘mischievous little breeze’, I’m not a scientist you know.”

Government officials in Florida are barred from using the terms “climate change”, “global warming”, “sustainable” and other related terms. Apparently, they’ll have to use the euphemism “nuisance flooding” in place of “sea-level rise”. One wonders what literary trick they’ll conjure up next time the state gets hit by a hurricane — “Oh, that? Just a ‘mischievous little breeze’, I’m not a scientist you know.”