Bill Hewlett. David Packard. Bill Gates. Steve Allen. Steve Jobs. Larry Ellison. Gordon Moore. Tech titans. Moguls of the microprocessor. Their names hold a key place in the founding and shaping of our technological evolution. That they catalyzed and helped create entire economic sectors goes without doubt. Yet, a deeper, objective analysis of market innovation shows that the view of the lone, great-man (or two) — combating and succeeding against all-comers — may be more of a self-perpetuating myth than actual reality. The idea that single, visionary individual drives history and shapes the future is but a long and enduring invention.

From Technology Review:

Since Steve Jobs’s death, in 2011, Elon Musk has emerged as the leading celebrity of Silicon Valley. Musk is the CEO of Tesla Motors, which produces electric cars; the CEO of SpaceX, which makes rockets; and the chairman of SolarCity, which provides solar power systems. A self-made billionaire, programmer, and engineer—as well as an inspiration for Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark in the Iron Man movies—he has been on the cover of Fortune and Time. In 2013, he was first on the Atlantic’s list of “today’s greatest inventors,” nominated by leaders at Yahoo, Oracle, and Google. To believers, Musk is steering the history of technology. As one profile described his mystique, his “brilliance, his vision, and the breadth of his ambition make him the one-man embodiment of the future.”

Musk’s companies have the potential to change their sectors in fundamental ways. Still, the stories around these advances—and around Musk’s role, in particular—can feel strangely outmoded.

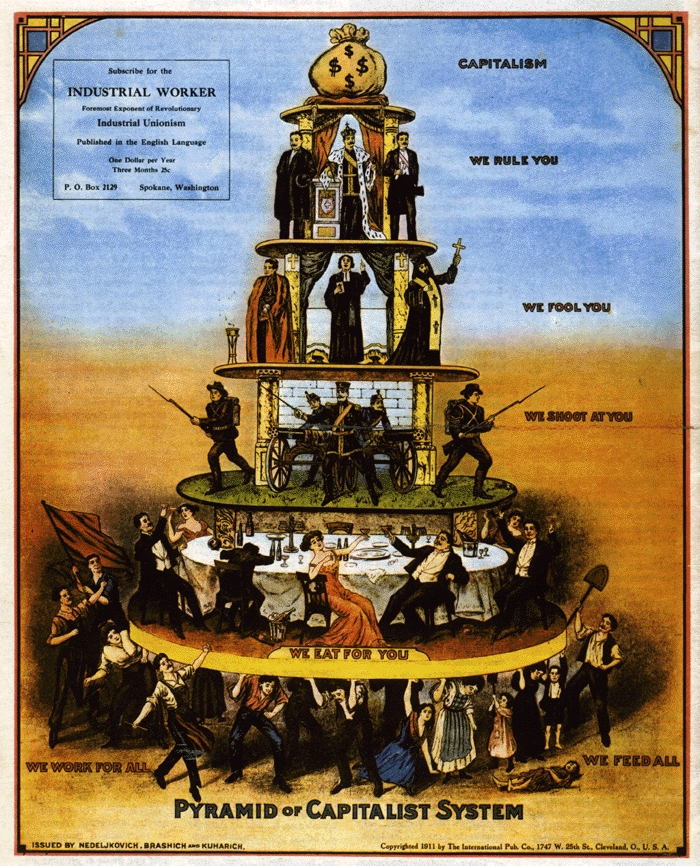

The idea of “great men” as engines of change grew popular in the 19th century. In 1840, the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle wrote that “the history of what man has accomplished in this world is at bottom the history of the Great Men who have worked here.” It wasn’t long, however, before critics questioned this one–dimensional view, arguing that historical change is driven by a complex mix of trends and not by any one person’s achievements. “All of those changes of which he is the proximate initiator have their chief causes in the generations he descended from,” Herbert Spencer wrote in 1873. And today, most historians of science and technology do not believe that major innovation is driven by “a lone inventor who relies only on his own imagination, drive, and intellect,” says Daniel Kevles, a historian at Yale. Scholars are “eager to identify and give due credit to significant people but also recognize that they are operating in a context which enables the work.” In other words, great leaders rely on the resources and opportunities available to them, which means they do not shape history as much as they are molded by the moments in which they live.

Musk’s success would not have been possible without, among other things, government funding for basic research and subsidies for electric cars and solar panels. Above all, he has benefited from a long series of innovations in batteries, solar cells, and space travel. He no more produced the technological landscape in which he operates than the Russians created the harsh winter that allowed them to vanquish Napoleon. Yet in the press and among venture capitalists, the great-man model of Musk persists, with headlines citing, for instance, “His Plan to Change the Way the World Uses Energy” and his own claim of “changing history.”

The problem with such portrayals is not merely that they are inaccurate and unfair to the many contributors to new technologies. By warping the popular understanding of how technologies develop, great-man myths threaten to undermine the structure that is actually necessary for future innovations.

Space cowboy

Elon Musk, the best-selling biography by business writer Ashlee Vance, describes Musk’s personal and professional trajectory—and seeks to explain how, exactly, the man’s repeated “willingness to tackle impossible things” has “turned him into a deity in Silicon Valley.”

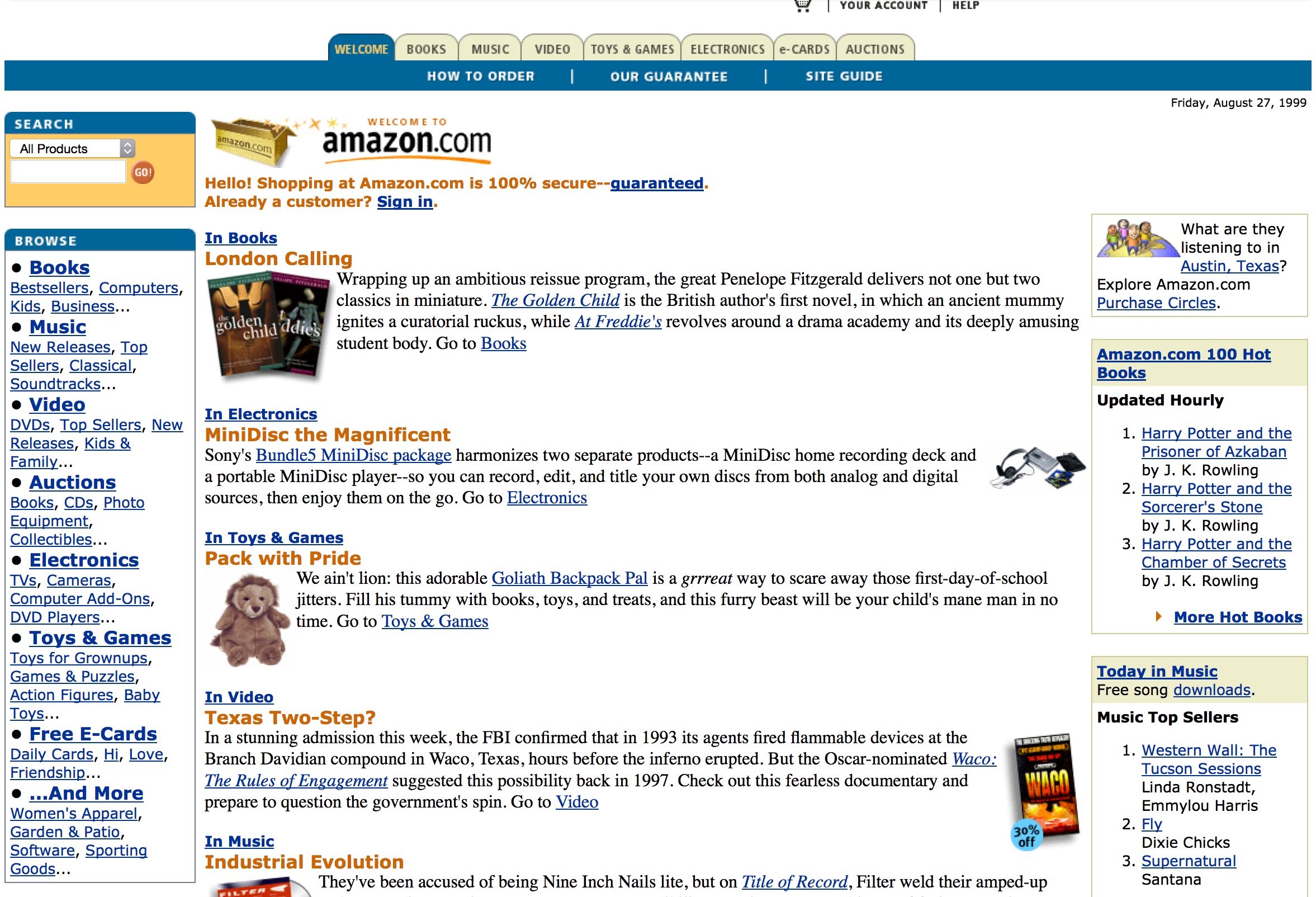

Born in South Africa in 1971, Musk moved to Canada at age 17; he took a job cleaning the boiler room of a lumber mill and then talked his way into an internship at a bank by cold-calling a top executive. After studying physics and economics in Canada and at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, he enrolled in a PhD program at Stanford but opted out after a couple of days. Instead, in 1995, he cofounded a company called Zip2, which provided an online map of businesses—“a primitive Google maps meets Yelp,” as Vance puts it. Although he was not the most polished coder, Musk worked around the clock and slept “on a beanbag next to his desk.” This drive is “what the VCs saw—that he was willing to stake his existence on building out this platform,” an early employee told Vance. After Compaq bought Zip2, in 1999, Musk helped found an online financial services company that eventually became PayPal. This was when he “began to hone his trademark style of entering an ultracomplex business and not letting the fact that he knew very little about the industry’s nuances bother him,” Vance writes.

When eBay bought PayPal for $1.5 billion, in 2002, Musk emerged with the wherewithal to pursue two passions he believed could change the world. He founded SpaceX with the goal of building cheaper rockets that would facilitate research and space travel. Investing over $100 million of his personal fortune, he hired engineers with aeronautics experience, built a factory in Los Angeles, and began to oversee test launches from a remote island between Hawaii and Guam. At the same time, Musk cofounded Tesla Motors to develop battery technology and electric cars. Over the years, he cultivated a media persona that was “part playboy, part space cowboy,” Vance writes.

Musk sells himself as a singular mover of mountains and does not like to share credit for his success. At SpaceX, in particular, the engineers “flew into a collective rage every time they caught Musk in the press claiming to have designed the Falcon rocket more or less by himself,” Vance writes, referring to one of the company’s early models. In fact, Musk depends heavily on people with more technical expertise in rockets and cars, more experience with aeronautics and energy, and perhaps more social grace in managing an organization. Those who survive under Musk tend to be workhorses willing to forgo public acclaim. At SpaceX, there is Gwynne Shotwell, the company president, who manages operations and oversees complex negotiations. At Tesla, there is JB Straubel, the chief technology officer, responsible for major technical advances. Shotwell and Straubel are among “the steady hands that will forever be expected to stay in the shadows,” writes Vance. (Martin Eberhard, one of the founders of Tesla and its first CEO, arguably contributed far more to its engineering achievements. He had a bitter feud with Musk and left the company years ago.)

…

Likewise, Musk’s success at Tesla is undergirded by public-sector investment and political support for clean tech. For starters, Tesla relies on lithium-ion batteries pioneered in the late 1980s with major funding from the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation. Tesla has benefited significantly from guaranteed loans and state and federal subsidies. In 2010, the company reached a loan agreement with the Department of Energy worth $465 million. (Under this arrangement, Tesla agreed to produce battery packs that other companies could benefit from and promised to manufacture electric cars in the United States.) In addition, Tesla has received $1.29 billion in tax incentives from Nevada, where it is building a “gigafactory” to produce batteries for cars and consumers. It has won an array of other loans and tax credits, plus rebates for its consumers, totaling another $1 billion, according to a recent series by the Los Angeles Times.

It is striking, then, that Musk insists on a success story that fails to acknowledge the importance of public-sector support. (He called the L.A. Times series “misleading and deceptive,” for instance, and told CNBC that “none of the government subsidies are necessary,” though he did admit they are “helpful.”)

If Musk’s unwillingness to look beyond himself sounds familiar, Steve Jobs provides a recent antecedent. Like Musk, who obsessed over Tesla cars’ door handles and touch screens and the layout of the SpaceX factory, Jobs brought a fierce intensity to product design, even if he did not envision the key features of the Mac, the iPod, or the iPhone. An accurate version of Apple’s story would give more acknowledgment not only to the work of other individuals, from designer Jonathan Ive on down, but also to the specific historical context in which Apple’s innovation occurred. “There is not a single key technology behind the iPhone that has not been state funded,” says economist Mazzucato. This includes the wireless networks, “the Internet, GPS, a touch-screen display, and … the voice-activated personal assistant Siri.” Apple has recombined these technologies impressively. But its achievements rest on many years of public-sector investment. To put it another way, do we really think that if Jobs and Musk had never come along, there would have been no smartphone revolution, no surge of interest in electric vehicles?

Read the entire story here.

Image: Titan Oceanus. Trevi Fountain, Rome. Public Domain.